![]()

When I find myself in times of trouble,

I go back to read Montaigne.

Seeking words of wisdom,

Read some more…

(to the tune of Let It Be, with apologies to the Beatles)

I was up late these last few nights reading Michel de Montaigne into the wee, dark hours. Although I used to read him rather frequently and found him an inspiration for several posts, some years back, I hadn’t picked him up in ages. But a passing mention in Sterne’s Tristam Shandy made me pick him up again starting with his long essay (69 pages in the Screech edition; 57 in the Frame translation) of “some verses of Virgil.” Which, in typical Montaigne fashion is less about the poet Virgil than about his views on aging, dying, sexuality, religion, marriage, virtue, honesty, and more. Strands of seemingly random thoughts woven into a longer piece. And, of course, abundantly sprinkled with quotations from a wide range of authors.

I was up late these last few nights reading Michel de Montaigne into the wee, dark hours. Although I used to read him rather frequently and found him an inspiration for several posts, some years back, I hadn’t picked him up in ages. But a passing mention in Sterne’s Tristam Shandy made me pick him up again starting with his long essay (69 pages in the Screech edition; 57 in the Frame translation) of “some verses of Virgil.” Which, in typical Montaigne fashion is less about the poet Virgil than about his views on aging, dying, sexuality, religion, marriage, virtue, honesty, and more. Strands of seemingly random thoughts woven into a longer piece. And, of course, abundantly sprinkled with quotations from a wide range of authors.

Montaigne’s greatness doesn’t lie with scientific breakthroughs, astounding discoveries, feats of endurance or strength: it lies with his ability and willingness to both question everything and to think through to his answers. Clearly, reasonably, openly, creatively. And then to put pen to paper and collect his thoughts for the world to read (the printing press has only been in use for just over a century when, in 1580, the Essays were first published). His essays are marvellously witty, thoughtful, insightful, and remarkably down-to-earth, even more than 400 years later.

You have to admire his willingness to commit to paper his doubts and uncertainties, as well as his passions and his views. This was the century of the Reformation, the Counter-reformation, of Henry VIII, Elizabeth I, and Martin Luther. The Roman Inquisition was in full swing, snaring Galileo, Copernicus, Giordano Bruno, and others in its repressive, orthodox net. Yet Montaigne wrote a spirited defense of the fifteenth-century theologian, Raymond Sebond, whose views about the nature of Christianity were under attack by church conservatives. That was a bold, and dangerous act.

Montaigne was, almost unheard-of for his time, frank and honest (sometimes brutally so) about his views, even when they ran counter to popular, church, or official opinions. His range of interests is broad, and he delights in throwing in tidbits from history, geography, agriculture, war, economics, fashion, philosophy… and in doing so gives us a picture of the 16th-century worldview (complementing that of my other favourite 16th-century author, Niccolo Machiavelli; but Montaigne is even more well-read — and even mentions Machiavelli twice).

Even when I don’t share his views, his faith, or his perspective — often, although not surprising given the chronological divide — I can respect his honesty, his integrity, and his passion for truth and understanding. But the sheer breadth of his vision and his willingness to ponder and question so many things and ideas accepted or rejected in his culture makes him heroic.

Montaigne didn’t just think about the “big” questions as some philosophers do: he thought about everyday life, even to the minutiae of habits and behaviour. He thought about his friends, his home, his body, his books, his sexuality, aging, his faith, children, poetry, ethics and morality, politics, the senses, reputation, emotions, education, buildings, sneezing, transportation, and even cannibals. Everything in the world made him curious, made his question, made him think, made him write and publish more than 100 essays (collected in three books) about what he perceived and thought. And for all of that, I delight in his words.

Montaigne didn’t just think about the “big” questions as some philosophers do: he thought about everyday life, even to the minutiae of habits and behaviour. He thought about his friends, his home, his body, his books, his sexuality, aging, his faith, children, poetry, ethics and morality, politics, the senses, reputation, emotions, education, buildings, sneezing, transportation, and even cannibals. Everything in the world made him curious, made his question, made him think, made him write and publish more than 100 essays (collected in three books) about what he perceived and thought. And for all of that, I delight in his words.

I started to read Montaigne again recently because I suppose I’m looking for comfortable advice about aging, mortality, and identity. Cancer can do that for you: put you in this sober mood to consider your life and what’s left of it. But I’m not maudlin about it: I just want some perspective. And not just about mortality: about aging, sensuality, friendship, morality…. and a lot more. In that cause, I’ve read Seneca, Marcus Aurelius, Cicero, Plato, Aristotle, Kant, Jung, Watts, Kübler-Ross, the Dalai Lama, and many others for their thoughts on these. Montaigne still strikes me as the best of them all, in large part because he was writing for himself.

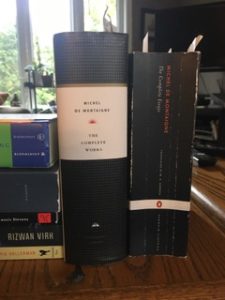

I tend to go back and forth between the Screech (2003 paperback edition) and Frame (hardcover 1957 translation, but also published in 2003) translations, although I find Screech’s version somewhat easier to read. And his footnotes help me identify Montaigne’s sources and references. Yet Frame was a more formal translator and, according to reviews I’ve read, hews closer to Montaigne’s own style. Plus the Frame edition also contains Montaigne’s letters, which are of interest to me.

(Montaigne wrote in Middle French, which is to modern French what Shakespearean English is to English today; more ornate and flowery than we tend to be, and with phrasing and style that may seem awkward or fusty to today’s readers. Translation can be tricky.)

I don’t always agree with him, mind you. He was a 16th-century French noble, Catholic, and with some now-antiquated ideas about many things, and lived in a world very remote and different from our own. His was the early Renaissance culture, A 21st-century humanist/secularist like me has many issues with some of his views. But so what? It’s not as if reading him will turn me into some chauvinist, Catholic, landowner. I read him for his motes of wit and wisdom, and to remind myself after reading social media posts, that there was a literate, thoughtful, engaging world once upon a time. And we can still visit it through books.