![]()

One of the comments in a rather lengthy letter presented to council recently was about hiring a CAO. The author demanded a “panel of qualified citizens appointed by an independent body* to oversee the recruitment, participate in interviews and the transparent selection process to fill the vacant position of Chief Administrative Officer for the Town of Collingwood.”

Aside from being wildly out of context in a letter ostensibly about local recreation facilities, that non-sequitur underscores a common misunderstanding about the nature of municipal governance and bureaucracy.

Many municipalities have CAOs or someone in that position – sometimes called a City Manager. However, there is no requirement in any provincial legislation for the town to have a CAO or any top-level administrative manager. We are legislated to have a clerk and a treasurer, period. It is entirely at the discretion of council whether to hire anyone else.

The old, but traditional, pyramid-shaped hierarchical management model has widening steps of management and staff descending from a single leader at the top. It may seem logical to have one person at the apex, but that’s more likely out of custom than out of necessity. Other models of management work as well, if not better (see below) in the public sector.

Reading far too often of the malfeasance and greed of corporate CEOs during the recent economic recession and downturn, especially in the financial sector, has considerably eroded any remnants of respect for the top dog position in the private sector. After working in several large private organizations based on that model, and having known and interacted with five town CAOs in the past 20 years, I am not convinced it is the most effective model for bureaucratic governance.

Having a single person at the apex of the municipal management pyramid means that person is the sole fulcrum for the interaction between council and staff. All of the planning, strategizing, communication, policy making and implementation roles are gathered in one person. Council’s direction and wishes are focused through the interpretation of that one person, too.The CAO is boss, yet also subservient at the same time.

Personalities can easily affect the relationship (both between CAO and council and CAO and staff). It requires someone who can put personalities aside, rise above the political milieu, and take on the often uncomfortable role as an objective conduit between council and staff, while trying to meet the needs and expectations of both the town and the transient politicians (a group which changes every few years).

It’s a difficult balancing act, one fraught with stress and potential conflict. It needs wisdom, patience, a Buddha-like calm, a good sense of humour, and a thick skin. Not everyone is suited for the political pushmi-pullyu role of municipal CAO.

Moving upwards in an organization is like being a juggler: you try to keep more balls in the air with every level change, until you finally reach the point at which there are either no more balls to add, or you can’t keep up everything you have in play, so you can’t move forward any more.

In every organization (including many municipalities), some top managers rise to their position because the promotion escalator is an automatic mechanism that gives people the opportunity to rise within the ranks based almost entirely on seniority. Basically, if you can sit there long enough in these companies, you’ll get promoted: sitzkrieg to reach the top salary slots.

In every organization (including many municipalities), some top managers rise to their position because the promotion escalator is an automatic mechanism that gives people the opportunity to rise within the ranks based almost entirely on seniority. Basically, if you can sit there long enough in these companies, you’ll get promoted: sitzkrieg to reach the top salary slots.

As a result, some people rise to levels outside their particular skill set, experience or comfort level and fail in their new role. This is known as the “Peter Principle“:

…in an organization where promotion is based on achievement, success, and merit, that organization’s members will eventually be promoted beyond their level of ability. The principle is commonly phrased, “employees tend to rise to their level of incompetence.” In more formal parlance, the effect could be stated as: employees tend to be given more authority until they cannot continue to work competently. It was formulated by Dr. Laurence J. Peter and Raymond Hull in their 1969 book The Peter Principle, a humorous treatise, which also introduced the “salutary science of hierarchiology.”

This is complemented by the rather more cynical and caustic “Dilbert Principle“:

…companies tend to systematically promote their least-competent employees to management (generally middle management), in order to limit the amount of damage they are capable of doing. In the Dilbert strip of February 5, 1995 Dogbert says that “leadership is nature’s way of removing morons from the productive flow.” Adams himself explained, “I wrote The Dilbert Principle around the concept that in many cases the least competent, least smart people are promoted, simply because they’re the ones you don’t want doing actual work. You want them ordering the doughnuts and yelling at people for not doing their assignments—you know, the easy work. Your heart surgeons and your computer programmers—your smart people—aren’t in management.”

Sometimes people are promoted just to get them out of the way. Dr. Peter also described this in his book, calling it “percussive sublimation”:

…the act of kicking a person upstairs (i.e. promoting him to management) to get him out of the way of productive employees.

He also described the “lateral arabesque” in which an

…incompetent worker is moved laterally or to another location with possibly a longer title.

So where does someone with ambition go after he or she reaches the top rung of the particular job ladder in a municipal organization? Usually to another organization or municipality where there are either more opportunities to move upwards, or where the pay and benefits are better (usually, but not always, associated with increased responsibilities). A lot of top municipal executives have a short (3-5 year) work span in any municipality as they work their way upwards.

Others may stay in place once they reach their topmost rung because they like the community and want to stay; others stay because they have been promoted outside their level of competence and have nowhere left to go. There they act as an anchor on the entire organization, making change, growth and innovation more difficult.

It’s difficult to decide who will best fill such an important role as CAO. Sometimes the apparent best choice in an interview turns out to be unsuited for their new position only after they have settled in; fulfilling the Peter Principle.

In the Forbes Magazine article, Seven Habits of Spectacularly Unsuccessful Executives, author Eric Jackson identifies:

Leaders who are invariably crisp and decisive tend to settle issues so quickly they have no opportunity to grasp the ramifications. Worse, because these leaders need to feel they have all the answers, they aren’t open to learning new ones.

Apparent decisiveness, he suggests, can mask a myopic, self-centred viewpoint.

Jackson also lambastes, those who “ruthlessly eliminate anyone who isn’t completely behind them”:

…CEOs who think their job is to instill belief in their vision also think that it is their job to get everyone to buy into it. Anyone who doesn’t rally to the cause is undermining the vision. Hesitant managers have a choice: Get with the plan or leave.

The problem with this approach is that it’s both unnecessary and destructive. CEOs don’t need to have everyone unanimously endorse their vision to have it carried out successfully. In fact, by eliminating all dissenting and contrasting viewpoints, destructive CEOs cut themselves off from their best chance of seeing and correcting problems as they arise.

I’;m sure you’ve known the “my way or the highway” types in your own past. I certainly have, and can list several companies that have ceased to exist because of this monolithic attitude.

For entrepreneurs and the Mitt Romney-CEOs, for the dog-eat-dog capitalism of corporate warfare, for those whose whose egos demand they be in control all by themselves and damn the underlings, this hierarchy seems the logical path to take because it can lead to ultimate, sole-sourced power.

A truly competent person may rise to the top in this environment, but there’s an equal chance that an incompetent person does – as Jackson’s article details.

This escalator-style corporate management model may not be the most appropriate for a municipality which should really be a cooperative, rather than competitive, environment. Municipalities have very different dynamics than private sector business.

Ideally, every CAO or top-level manager should have a wide range of skills (as per enotes.com):

Regardless of organizational level, all managers must have five critical skills: technical skill, interpersonal skill, conceptual skill, diagnostic skill, and political skill.

However, it’s unlikely any single person has all of these in sufficient supply. Not to belittle anyone who has held that role, but these skills are big shoes to fill. While a good manager will delegate some responsibilities to those who have the complementary skills, it’s not easy to release the reins of power once you’ve been given them.

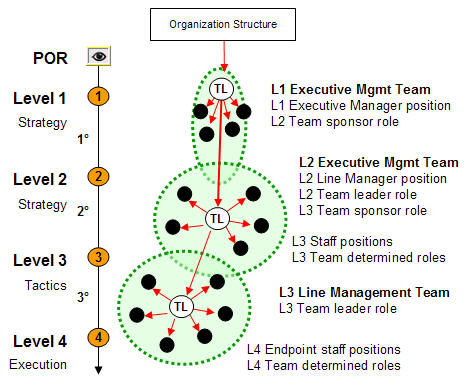

That’s where team management comes to the fore. A team can supplement each other’s weaknesses by providing a mix of skills, talents, and personalities to strengthen the group: a gestalt, where the whole is greater than the sum of the individual parts. As also noted on enotes.com:

A team is a group of individuals with complementary skills who work together to achieve a common goal. That is, each team member has different capabilities, yet they collaborate to perform tasks. Many organizations are now using teams more frequently to accomplish work because they may be capable of performing at a level higher than that of individual employees. Additionally, teams tend to be more successful when tasks require speed, innovation, integration of functions, and a complex and rapidly changing environment.

Another type of managerial position in an organization that uses teams is the team leader, who is sometimes called a project manager, a program manager, or task force leader. This person manages the team by acting as a facilitator and catalyst. He or she may also engage in work to help accomplish the team’s goals. Some teams do not have leaders, but instead are self-managed. Members of self-managed teams hold each other accountable for the team’s goals and manage one another without the presence of a specific leader.

This is like the model Collingwood has taken and, in the months since we implemented it, it has proven far more successful than anyone imagined. To be clear: the position of CAO is technically not vacant: Council appointed Mr. Ed Houghton in April as Acting CAO (he currently does so without any additional remuneration, by the way). However, he serves as the team leader, the catalyst, rather than the overlord.

Others on the executive team include the town’s treasurer (Ms. Leonard), our clerk (Ms. Almas), and the Collus Director of Operations (Mr. Irwin). These four people pool a considerable wealth of experience, talent and perspectives.

Teams are essentially mutually-supportive, multi-tasking units, whose members have the ability to deal with multiple issues and activities simultaneously, yet work on collective goals. The group approach parallels current social trends being played out online, in social media. As Luc Galoppin writes:

Successful organizations are those who are aware of that shift and tap into the new literacy of collaboration that social media has brought us. The result is a new balance between hierarchy and community that is called social architecture… We still need hierarchy and control to get things done. The only difference with the old days is that control will only get you half-way. The Industrial Revolution is over. Today, getting things done requires an extra layer on top of hierarchy. We need to re-wire our organizations and tap into the potential of communities, tribes, movements, problems and solutions. Each of these communities wants to be hosted. And you need those communities to get results in today’s economy.

Galoppin makes some salient points about the shift from the traditional hierarchy to a more community- or tribe-based based management, one in which influence and collaboration replace the old “command-and-control” structures. In that sense, Collingwood is ahead of the curve because we have already moved beyond the traditional, but often fragile, hierarchical models.

Galoppin makes some salient points about the shift from the traditional hierarchy to a more community- or tribe-based based management, one in which influence and collaboration replace the old “command-and-control” structures. In that sense, Collingwood is ahead of the curve because we have already moved beyond the traditional, but often fragile, hierarchical models.

What we have done is de-layer the old hierarchy and empower the middle-level management. In doing so, it seems a traditional CAO position is proving to be a redundant level of management and unnecessary bureaucracy we can afford to eschew. We have one less level in the decision-making process, but more decision makers. And yet our expenses are lower.

In a study of delayering management practices, P. Kettley wrote,

Central to the new model of organisation in the 1990s is a flatter structure, achieved by a reduction in the number of layers in the management hierarchy. Such a structure is becoming synonymous in popular management theory with bureaucracy busting, faster decision making, shorter communication paths, stimulating local innovation and a high involvement style of management…

For some, the achievement of such savings is the primary objective of their restructuring initiative. For others, a flatter structure is the route to freedom from bureaucracy, speedier communication and the development of a customer focused culture in which team working and high involvement working practices will thrive.

A flatter organisation is achieved in several ways. First, by the elimination or automation of management activities and the subsequent redundancy of those posts performing them. Second, as the result of unnecessary and costly overlaps of accountability being identified and reallocated.

Whether or not this will continue to be the model for town management, I can’t say. I can only observe that it has proven itself in the short time we have operated with it and I would be hesitant to vote to return to the older, less collaborative and certainly more expensive model with a CAO alone at the top of the pyramid.

Council has also expressed its collective support for this inclusive, team-management, collaborative approach. Town hall is functioning better and more smoothly than I’ve ever seen it in 20 years. Staff morale is high and the relationship between Mr. Houghton’s team and council is excellent. There is no need to go to the expense or effort to fill the role with an outsider.

~~~~~

* As for the group’s unrealistic demand that outsiders determine staff requirements, the right to appoint or dismiss senior staff rests solely with the elected council. Under the requirements of the Municipal Act, personnel issues cannot even be discussed with those who are not authorized by the legislation. The Municipal Act does not allow a group of unelected citizens to control the actions of elected representatives or staff with regard to hiring personnel or to determine staffing levels.

Interesting article Ian. Thanks for your time on this. I found this statement the most interesting “Jackson also lambastes, those who “ruthlessly eliminate anyone who isn’t completely behind them”: 😉

NOT referring to the current CAO btw.

“panel of qualified citizens appointed by an independent body* to oversee the recruitment, participate in interviews and the transparent selection process to fill the vacant position of Chief Administrative Officer for the Town of Collingwood.”

Ah, yes… The conservative credo…

“Any means is justified to get my way.”

Rather observant of you, Bill. There is a certain rabidly Conservative element behind these demands; members of a group that although disbanded (and discredited) some years ago, still worms its way into local causes, hijacking the issues for their own agenda.