![]()

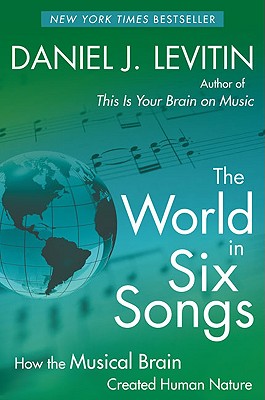

Author, musician and neuroscientist Daniel Levitin says all music can be classified into a mere six types of song. That’s part of the premise in his 2009 book, The World in Six Songs. I recently started reading it and it has opened some interesting areas of thought for me.*

Author, musician and neuroscientist Daniel Levitin says all music can be classified into a mere six types of song. That’s part of the premise in his 2009 book, The World in Six Songs. I recently started reading it and it has opened some interesting areas of thought for me.*

A mere six fundamental themes in song, Levitin writes: friendship, joy, comfort, religion, knowledge and love. And he provides a chapter for each in what is a literary combination of sciences, music, social commentary, cultural anthropology and personal reminiscence. And he offers a lot of conjecture that, while not necessarily provable, is always entertaining and thought-provoking.

That reductionism seems like a challenge to the reader. My first thought was, are these six discrete or can songs overlap and share categories? What about music without lyrics? Soundtracks? Where do they fit? What about non-western music? What about satire and comedy songs? Storytelling songs? Songs of mourning and lament? What about Gilbert and Sullivan?

What about Bob Dylan? I listen to and play a lot of Dylan’s music and there are some songs that I have never been able to classify or explain, even after decades of familiarity with them. Where do you put a song like Stuck Inside of Memphis with the Mobile Blues Again? or All The Tired Horses? The Gates of Eden?

Or Bach’s Goldberg Variations? The second movement of Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 1? Leo Kottke doing Jesu Joy of Man’s Desiring on slide guitar? John Fahey’s The Yellow Princess? Puccini’s Un bel di vedremo from Madame Butterfly? How can a song in a different language you don’t understand move a listener to weep openly? It’s not simply the lyrics. Music reaches inside us in ways we really don’t understand.

And, of course, I immediately came up with my own mental list of songs and tried to fit them into Levitin’s boxes, often without finding a comfortable fit. But that’s part of the fun. Willie the Pimp? the Velvet Underground’s The Gift? The WCPAEB’;s Watch Yourself? Too many to list that don’t fit (as I read it) into comfortable categories.

What about Honshirabe? It’s the classic Zen piece for solo shakuhachi; a stunningly beautiful, haunting piece that speaks volumes to the listener about Japanese culture without lyrics. It is powerful enough to stop me in my tracks and force me to sy stand still and listen, and can easily move me to tears. Where does that fit in the six songs?

Music is not simply entertainment, Levitin argues: it’s an evolutionary force that moves, changes and advances our species – and our civilizations. It has evolved within us, is part of our brain’s function and has expressed itself through our developing cultures and civilizations. And I agree with his take on that. I can’t think of a single culture or civilization that has developed without music integral to its growth.

Of course, we have a gap in our understanding of how music was performed and sounded before cultures developed a method of writing those forms in a recognizable format. We know, for example, that the Sumerians built musical instruments, and used a diatonic scale, but we really don’t know what their music sounded like, or what it was used for. We’re just guessing because they, and most ancient cultures, didn’t have an organized method of writing out music like we have today (although there have been some advances in this area)

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2H8_13x3JaI]

We also know that in most cultures, music is not isolated from other arts, from religion, or civic activity. Music is closely associated with dance, civic and religious ritual, prayer, war, celebration and performance – plays and oral recitations (poetry). In fact there may not have been much if any of a separation in the past between dance, music, singing and performance.

And singing appears to have been a far more public activity worldwide pre-1950. It seems technology has increasingly reduced the public aspect of vocalization (just my own hypothesis). But until WW2, music and public singing was used in politics, religion, and war – something hardly done today outside national anthems.

There’s a scene in the movie Cabaret where one young man starts singing “Tomorrow Belongs to Me” – a song popular with the growing Nazi movement – and people stand up and join in. It’s both frightening and moving because that’s the power of music.

Music – and public singing – was part of the popular political and social landscape until fairly recently. Parties and movements had their songs. It seems we have become less participants and more passive listeners since the 1950s (although there was a revival of collective song in the 1960s during civil rights and anti-discrimination movements).

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=29Mg6Gfh9Co]

That may simply be my own perspective, but it’s based on experience.

About a dozen years ago, we attended a local musical performance of WW2 songs, with Susan’s (now deceased) parents. The seniors in the audience – the large percentage – sang along to the songs they learned in their youth, the songs that held them together in the war, that bound them in adversity. My own parents’ songs. And then so too did the others, we younger members of the audience; joining in when they did – bridging generations.

It was deeply moving. I still get goosebumps when I think of the grey-haired audience softly singing along with “We’ll Meet Again” and seeing their faces, softly lit by the table candles, transported back 50-60 years, some with tears in their eyes. They still remembered every word, still felt the emotions, and through the music they recalled the times, their friends, the losses, the victories, the passion.

Music does that to us. It can move us in ways that are beyond our control, beyond simple explanation, unexpected and deep. Some songs are so emotionally powerful they can overcome us. Listen to this piece, recorded by the New York Rock & Roll Ensemble in 1971, and tell me it doesn’t move you:

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CKHzFobg0WU]

(It is perhaps my all-time favourite song; the song I think of when I think of Susan: I will always be beside you. It is the musical surrogate for the emotions I feel for her. When I hear it I think of the someone I will always want to have with me. I can be brought to tears by it. Music does that.)

But it’s not mere sentimentality that moves us. I remember the political and social impact that Garland Jeffreys’ song, Wild in the Streets had when it came out. It might have been the street anthem – temporary as any pop music anthem is – of the times and thus has stayed with me:

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3RzBZsOeqOQ]

Whether Levitin’s particular arguments for that co-evolution of music and humanity hold water doesn’t really matter. No one can confidently second-guess why natural selection works the way it does (and such guesses often drift into Lamarckism….). The act of making a hypothesis is what stirs the debate. And besides, music isn’t itself organic, but rather more in the realm of the meme, an area we are still trying to understand.

As an amateur musician, one with an interest in many other areas, I have a fascination with music’s impact and effects throughout history. Why do some songs move one person, but bore another? Why can we remember songs and lyrics better than prose? Why do some cultures have different rhythms, sounds and tones? Why does music mean so much to us?

Music been with us since at least our Neanderthal ancestors at least 40,000 years ago – what is it that fulfills a basic human need for music? Levitin would say it’s an organic part of us, and I would agree.

There’s a quote from Sting on Levitin’s site:

Music seems to have an almost willful, evasive quality, defying simple explanation, so that the more we find out, the more there is to know, leaving its power and mystery intact, however much we may dig and delve…”

Evasive or not, Levitin attempts to pin it down and confine it. Yet music, in Levitin’s writing and despite the cobnstrictions of analysis, still holds a sense of wonder, and hasn’t been entirely washed out by what is to me the accelerating commercialism and co-opting of popular music for commercial purposes (think about it when you hear the Rolling Stones tunes played on bland synthesizer or string section in the supermarket next visit to pick up milk…).

On a personal note, music moves me constantly, continually, deeply. I awake with songs in my dreams, I walk the dogs to the beat of songs I hear in my head. I hear music and rhythm in everything. I am driven almost to obsession to make music, to play along with music I hear, to arrange and recreate songs for my current instruments.

I can’t fit everything I hear, I see, I perceive in music into Dr. Levitin’s neat categories, but I agree with him about music’s wide reach and impact on our cultural and social development. It is within us, genetic, evolutionary and organic. There is no life without music. At least one that’s worth living, as I see it.

Playing along with a group of ukulele players, many of them who are newcomers to making music, I can appreciate the power – the collectivizing, healing, invigorating and ameliorating power – of music. I play with them because it fulfills a need to make music, to participate in music.

Music most of all, for me, is a means for expression. And in doing so I connect to the “starry dynamo in the machinery of night” as Allen Ginsberg called it… we are all his “angelheaded hipsters burning for the ancient heavenly connection…” to the music.

~~~~~~

* Levitin’s book has been praised, but also criticized on several levels. For example, Susan Tomes in the Guardian wrote: “…a song lyric is only part of a song, and doesn’t conjure up the music if you don’t already know it. Reading this book is, in fact, a bit like reading the lyrics of an unknown song: the music seems to lie tantalisingly out of reach.” But I still feel the book is a worthwhile read because it spawns discussion and debate among readers.