![]()

Every day, for an hour or two, I kill demons. Or I build houses and shopping malls. Sometimes I command armies in battle. Or fly an airplane into a foreign airport. I might manage a hospital, build a settlement on Mars, lead a band of survivors after a nuclear holocaust, hunt Nazis as a sniper in WWII, drive a tank onto the sands at Omaha Beach, move Roman legions around the Mediterranean, build an empire, sail with a fleet of starships into the vastness of space, trade for equipment with aliens on a far distant planet, craft my own Jurassic Park, perform quests for a magician, or dig a deep mine under my house to look for crafting items. All done in any one of a hundred or so computer games I own.*

For me, gaming is interactive fiction: engaging in virtual stories. Like books, games let me escape into another world, to be someone else, to live in a different time and place, to play out a role. I am not a mere spectator in a game; I am a participant. My decisions matter in these virtual worlds.

“I grow old, always learning many things.”

Solon Nomographos, Fragment 18.1

I’ve learned many things as I played. I’ve learned that infrastructure and planning matter when growing a city; that armoured units are vulnerable to enemy attacks without supporting infantry; that trying to land a small plane in a crosswind is tricky and dangerous; that a hospital without sufficient support staff can’t handle the patient load; that a population without a supply of food soon withers, that cavalry can’t charge uphill very well; that gravity wells can drag your ship into a star if you get too close, and that having a good supply of health potions is as important as having a good weapon when killing demons.

Okay, maybe not everything I’ve learned through my gaming has been useful in the real world. But almost every game is a learning experience, even if that education is internal to the game itself. And any sort of learning is good for keeping the brain nimble and to exercise the memory. I always remind myself that Cicero learned to read and write Greek in his “old age” (De Senectute, 8). Learning while playing a game seems much easier and less taxing on my memory than learning Greek.

…for he thought that all time was wasted which was not spent on study.

Pliny the Elder, Letters 3.5

Play is essential for a balanced life; more so when you are a senior. Play keeps our minds active, our brains agile, and our personalities from ossifying into that funless, “mature” state far too many adults descend into. And while we’re in lockdown, computers are the ideal platform for playing on. The options within computer gaming are vast.

Most games (including computer, video, PC, console, tablet, and phone games) fall into two broad categories: storytelling and puzzle-solving. These can mix in the same game, of course, and there are many sub-genres like strategy, military, role-playing, racing, simulation, adventure, wargames, card games, tower defence, 4X games (Explore, Expand, Exploit, and Exterminate), walking and flight simulators, hidden objects, and so on.

Computer games have the advantage over board games in that they can usually be played solitaire, don’t need additional space to play, and are not limited by the restrictions of physical components. Plus, you can stop and save games to continue later, rather than have to complete them in one sitting.

Computer games have increased remarkably in complexity, depth, and immersion potential over the past few decades since I began playing them. This has been thanks to a confluence of improved technology (faster processors, more memory, more disk space, networking), better graphics processors, plus improved scripting and coding.

A game like Witcher III, for example, offers hundreds of interactions with computer-controlled non-player, AI characters (called NPCs, many of which have lengthy voice-acted conversations available); between 125 and 150 sq. km to explore (walk, run, ride a horse, sail a boat, swim); hundreds of quests, side quests, and treasure hunts; innumerable monsters (land, sea, and air) and enemies to defeat; all of which takes hundreds of hours of play to complete even once. And that doesn’t include the available expansions (downloadable content, or DLC) that open new areas and quests to explore. The time one can spend in a game like this is considerable: at least 100 hours is required to play through it once (and gamers often play it more than once at different difficulty settings).

(Not to forget the large online communities, fan sites, and forums that offer tips, gameplay hints, secrets, quest solutions, maps, and support for pretty much every game you will ever play.)

Some games, like the Sherlock Holmes mysteries, hidden-object games, and adventures like Myst merge both role-playing and puzzle-solving in equal share. Many first-person shooters (FPS)** require players to figure out how to accomplish difficult goals such as reaching a location, eliminating enemies, acquiring an object, or not being discovered, as well as playing as the protagonist on a mission.

Puzzle-solving games include card games; traditional board games like chess, checkers, and go; cribbage; jigsaw puzzles; trivia and knowledge games; most educational games; hidden objects; mahjong; crossword and word puzzles; sudoku and logic games; and solitaire puzzle games. These are also available in computer form, sometimes with additional elements not available in the board game (for example, in the computerized Clue game, you role-play your character and interact with the other players in that role).

Many of the side-scrolling “platformer” (jumping) games that gained popularity with the Super Mario series are also puzzle-solving games. Even the old arcade games from Pong to Pacman are puzzle-solving games. These and other action-oriented games also help develop reflexes and hand-eye coordination.

Storytelling games also include a wide range of genres, but the story may be implicit, not explicit. The classic Monopoly, Risk, And Clue (aka Cluedo) board games are actually storytelling games, even if the story is not explicitly stated. Players will naturally make up the stories in their own heads as they play, rather than simply move pieces and troll dice.

Players fighting for the ruins of Stalingrad on a wargame board are not merely moving cardboard counters around to simulate military units: they are playing the roles of generals leading troops into combat, engaged in a bitter contest over territory. Players in Monopoly are viciously competing capitalists, buying, selling, investing, suffering the ups and downs of chance as they crawl their way towards the top at the expense of the other players. Each move in a board game is part of the player’s story. But many modern computer games come with fully-fleshed plots, character interactions, voice action, cut scenes, and activities (like quests) that develop and enhance the player’s character. In many, the player’s choices affect the way the non-player characters (NPCs) interact with the player, too; the virtual world feels and behaves more like the real one.

Storytelling is critically important to humans. Stories are hardwired into us. They have been part of our cultures, our social development, our religions, our politics, and our survival since humans first learned to speak. We have learned from stories how to be human, how to interact, how to fight, how to hunt, how to cook, how to build, how to worship, how to be good, how to avoid danger, how to rule, how to love. Many of the very oldest written records are of stories: Gilgamesh, Genesis, the acts of the pharaohs, the exploits of Chinese kings and Indian princes. Gods and humans intertwine in our literature. Computer games are merely a recent platform for our storytelling.

I got to thinking about gaming when I read a short article in the most recent edition of the Costco Connection (Tech Connection in the March/April, 2021 issue) about seniors playing video games***. I chuckled a bit when I read it, because it’s by a much younger person who seems to think seniors are foreign to gaming and computers and too old and slow to play “action” games. Piffle. We’re not incapable simply because we’re older.

Hardly a day goes by when I am not playing some game on my current PC. Many are action-oriented and I’m far from the only senior playing WoW or WoT. Online chat tells me we old codgers are doing as well if not better than the youngsters in the game (we’re generally more polite and well-spoken, too, but that’s another post).

My fingers may not be as nimble as some teenager’s, but I can still battle a horde of demons in Diablo III or take on a boss in WoW and come out alive with my treasures intact. Just because a person is old doesn’t mean they have lost their senses, or their wits, their determination, or their capacity for fun.

The article suggests that playing video games can be healthy for seniors because it “could stave off mild cognitive impairment, and perhaps even prevent Alzheimer’s disease, for those between the ages of 55 and 75.” That’s based on a study done by the University of Montreal, but it was a small sample of only 33 adults. Still, I agree with the premise (after all, I’ve been doing this for the past five decades*). But games are not simply therapy.

The article’s author quotes other studies that indicate “cognitive benefits, including mental exercise, fun, and improvements in attentional focus, memory, reaction speed, problem-solving, and reasoning from digital gameplay.” (I assume when the authors write “digital” the authors mean computer as opposed to fingers.) Sure, but that’s like saying a car is designed to make its wheels go ’round. There’s a lot more to it than that, and for games, I believe the interactive story is a more important element because it engages the brain, not simply the reflexes.

(In many of the role-playing games I play, I must remember tortuous paths through dungeons, woods, or some virtual city; to recall how to get in and out of a location to find a treasure or fulfill a quest; to remember which characters I need to return to for trade or instructions; to remember which keys on the keyboard activate spells, attacks, healing, change weapons, pull up a map or my inventory. These games really help keep your memory sharp and active.)

I take umbrage over the article’s comment that “seniors tend to prefer card and puzzle games to the more action-oriented fare that younger gamers embrace.” Condescending codswallop. Why would we be any less prone to playing action games? Even if we may not be as physically active as when we were younger, our brains are not sedentary, nor is our imagination limited by age.

I still play all of these types of games, and more. I have a collection of more than 150 games on my computer, many of them the sort of action-oriented computer game the author says I shouldn’t prefer. I also have many complex, time-consuming, and thought-oriented, deeply-immersive strategy games that range in subject from the Roman Empire to empires in space. Why does he assume seniors would not enjoy these more demanding, more interactive and immersive games?

Okay, I admit I am not your typical senior, and my long history of board gaming has allowed me to enjoy computer games for longer than many. But it’s not merely the accomplishment-competitive nature of many games I enjoy. I like the storytelling; the immersion in another world or universe as if I was participating in a book. I like putting myself into the mindset of a leader of a band of settlers, a general moving his army against an enemy, a warrior or a wizard facing hostile orcs and trolls, the captain of a starship, a railroad tycoon, the head of a medieval family eager to rise in the nobility, a restaurant manager, a city planner, a detective, a farmer, a WWII sniper, and even a car mechanic.

I like having to make decisions in those games, interact with other players or computer characters (NPCs or Non-Player Characters), solve problems, fight for survival, achieve goals. I get a sense of accomplishment from building my little village into a thriving, modern city, from raising my stone-age people to a towering technological civilization, from breaking through enemy lines with my tanks and infantry to take a key city, from accomplishing quests in a fantasy game, from seeing my family rise to the forefront of the nobility over several generations to take the throne, or seeing my trade routes spread across the galaxy as I build my financial empire. There’s a satisfaction in accomplishments in those games and I believe others my age would agree.

But most of all, I like having fun. Games are entertainment and play. And we all need to play to stay young, at least young at heart. Games also give me a lot of brain stimulation, keep my memory working, make me solve puzzles, make decisions, weigh options and develop my imagination. It’s a different form of neural exercise from reading a book or writing posts here on my blog, but it’s a helluva lot more stimulating than binge-watching a TV series. And far too many people do that during the lockdowns.

~~~~~

* I’ve been playing games on my computers ever since I bought my first TRS-80, in 1977. I’ve not stopped, although there were times when I didn’t game daily or even weekly. I played the business/trading game, Santa Paravia And Fiumaccio in 1978, the first text adventure game, Zork, in 1979 (there’s a whole site dedicated to archiving vintage interactive fiction and adventures here) I played Taipan! on my TRS-80 in 1982 (you can still play it in a port from the Apple II version online here). I played Wizardry on an Apple II in 1980, the original Castle Wolfenstein in 1981, and Doom in 1993 (both on IBM PCs), Diablo II and III (2000 and 2012), Call of Duty from 2003 to 2007. I’ve been playing World of Warcraft (WoW) since 2005 or ’06; World of Tanks (WoT) for a decade. I’ve played every edition of the SimCity and Civilization games since they were first released (1989 and 1991, respectively). Plus there are literally hundreds of others I have played.

I’ve been singing the praises of computer gaming, writing about gaming, reviewing games, and even beta-testing them since I got my first computer in 1977. I learned to program (and practice my typing skills) with the TRS-80, Apple II, Atari 800, Kaypro, and others. I was able to write my first book, Mapping the Atari, because I learned to code in BASIC from tinkering with games.

Back in the early-to-mid 1970s, I played chess a lot: many nights were spent in intense competition with friends and neighbours. In the mid-70s, I worked at a downtown Toronto game store where I discovered go and then complex strategy and war games like the Avalon-Hill and SPI lines, and I played them obsessively instead of chess (I still have some in my closet), I played the original Dungeons & Dragons game, then, too.

Once I was reasonably proficient with computers, I wrote a regular column on computer games for MOVES magazine in the 1980s, focusing on strategy and wargames. I also wrote columns and feature articles for several computer magazines like ANTIC and ST-LOG for many years in which I discussed and reviewed computer games. Gaming has been in my blood for the past five decades.

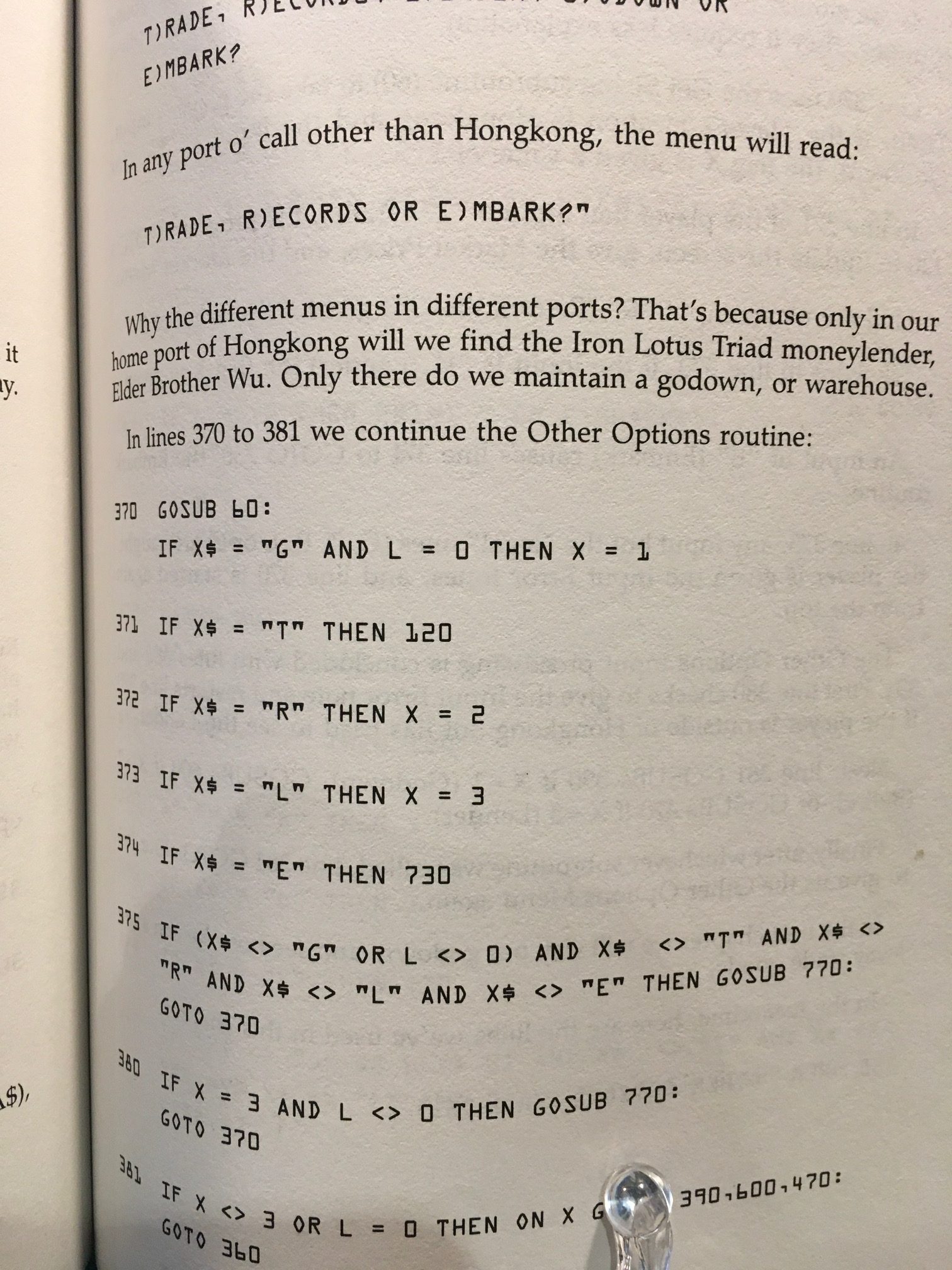

While sorting some books recently, I found several titles from the 1970s and ’80s about computer programming, simulation, and game design, including Taipan!, a game loosely based on the James Clavell novel of that name. The cover of a book about the game explaining its BASIC code is shown above.

Of course, long gone are the days when amateurs like me can hack away at programs and tweak them to learn and experiment like I did. No one codes in BASIC these days, and computer games are exponentially more complex, more resource-intensive, more interactive than anything I tinkered with. The number of calculations required in an online, multi-player is mind-boggling, especially one in which players interact in a real-time, 3D environment.

I’ve been playing first-person shooters (FPS or shooters), role-playing games (RPGs), massive, multiplayer, online, role-playing games (MMORPGs), flight simulators, combat simulators since the days of Castle Wolfenstein (1981) and Doom (1993), the two pioneer shooters. I played the original SimCity and Civilization games, too. I played the Call of Duty and Ghost Recon game franchises for their first decade.

** In FPS games the character may not be a ‘shooter’ but could be a pirate, crusader, archer, thief, magician, pilot, etc. Players perform the role in a “through the eyes” or first-person viewpoint. Some games put the viewpoint into a third-person location (over-the-shoulder view; above and behind the main character).

*** Are video games the same as computer games? And what about console games? Well, it’s complicated. Some clarification is required. The Cambridge dictionary online defines a video game as:

a game in which the player controls moving pictures on a screen by pushing buttons;

a game in which the player controls moving pictures on a television screen by pressing buttons or moving a short handle:

See the first problem? Computers don’t have “buttons” or “short handles.” Accessory game controllers have them, but most computer games are controlled with the keyboard and mouse. Yes, you can use a game controlled on some computer games, and games like flight simulators can be best played with a joystick controller. Not to mention that computer games are played on a monitor screen, seldom on a television screen. This definition is more suited to a console game.

Merriam Webster’s definition is more open:

an electronic game in which players control images on a video screen

Uh, yes, but that’s like describing a car as an “assemblage of metal and plastic components which drivers control by moving pedals and a steering wheel.” The Collins dictionary offers this:

A video game is a computer game that you play by using controls or buttons to move images on a screen.

That misses the mark because there is a commonly-accepted industry identification that separates computer and console games; even though consoles are computers, they are specific in their functions (and have different input devices). Yes, some games are published on both platforms, but their controls differ. And what about tablets and phones? None of these definitions speak to the platform and the technologies involved.

All of these definitions miss the point: it’s a game first. The Chicago School of Media Theory tackles the issue more succinctly:

Games themselves, video or not, are about the interaction and experience with “the subject as a system of rules” … much as a painting or a photograph is about experiencing the subject as an image rather than as a corporeal thing or scene.

Marshall McLuhan writes, “Games are popular art, collective, social reactions to the main drive or action of any culture” … Video games are the same, although they often manifest in higher narrative form and immersion than board games or sporting events.

https://medicalxpress.com/news/2021-03-game-thrones-reveals-power-fiction.html

Game of thrones’ study reveals the power of fiction on the mind

…without the sense of play as an essential element in literature, we would have to do without much of Chaucer, Shakespeare, Joyce, Proust, Nabokov – for in a sense all art is a game, the game of putting form to matter…

Rose A. Zimbardo and Neil. D. Isaacs in Understanding The Lord of the Rings: The Best of Tolkien Criticism (Houghton Mifflin,2004)

There is also an Interactive Fiction Technology Foundation (IFTF) that describes itself:

The oundation’s interactive fiction database contains many computer games with storytelling components.

Here’s a good YouTube review of Streets of Rogue, a computer game that offers a wide range of player agency, thus developing player stories in it:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=syu7WyCyOpU

I’m not moved by the pixelated, pseudo-retro graphics, the action-oriented gameplay, or the interface, but the premise of open-ended gameplay is appealing enough for me to seriously consider buying it.