![]()

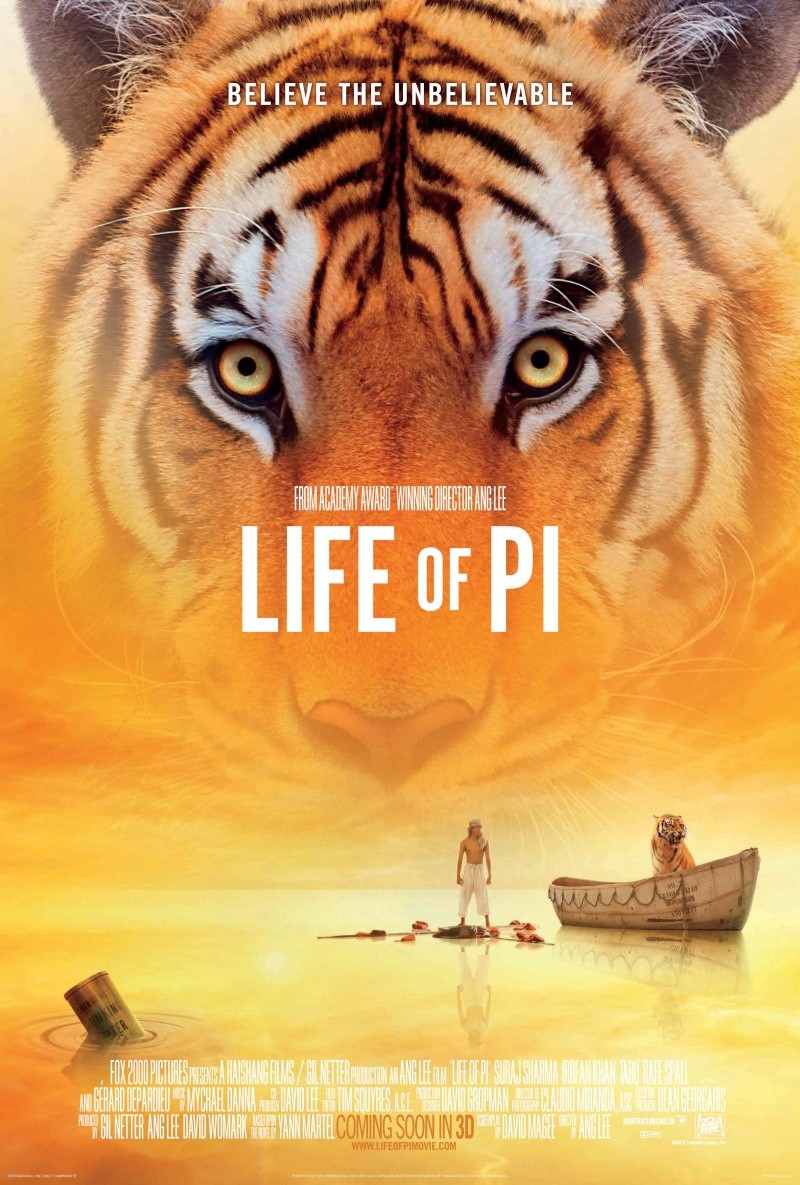

We watched Life of Pi last night, a film that has garnered much critical acclaim and won four coveted Oscar awards (although it has not been without controversies). I had struggled somewhat with the book (for reasons given below), but the lavish praise for the film made me decide to try again.

We watched Life of Pi last night, a film that has garnered much critical acclaim and won four coveted Oscar awards (although it has not been without controversies). I had struggled somewhat with the book (for reasons given below), but the lavish praise for the film made me decide to try again.

I had read about the movie’s stunning camera work and CGI graphics, and these do not disappoint. It’s a beautiful film, and the CGI is amazingly lifelike. I puzzled over what was real and not in many scenes. But the story itself…

While sometimes described as a “fantasy adventure”, the novel is really an allegory about the search for meaning in religion. It’s also about the relativity of truth.

One of the delights of fiction is than an author can conjure up a situation, a landscape, an event and give his or her characters the chance to explore that imagined world and determine what it means to be human under those circumstances. That’s one reason I like science fiction: it has no boundaries to the imagination. But sometimes an author is trying not just to use this world to explore the human condition, but rather make a point, to teach, to pontificate what he or she believes is the message we readers need to absorb.

I felt Martel’s message, lumbering through the pages, was heavier-handed than his actual words. And that too often he meandered down his path rather than walked us towards it (compare the 300-plus pages of Life of Pi to Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s brief little allegory, The Little Prince). Even Paul Coelho, that author of so many allegories, is briefer in his tales of self-discovery.

Martel’s writing is fairly smooth and light throughout most of the book, but I personally found it dragged, especially in the beginning. The core of the tale – Pi’s survival at sea with a tiger – doesn’t being until Chapter 37, a third of the way into the story. By then I was muttering “get on with it” to myself as I read through the pages.

The tale – when it finally began – struck me like a modernized Book of Job: a human suffering the vicissitudes of life and his hostile environment while struggling to keep faith, illogically at times, with an arbitrary, unresponsive or sometimes downright cruel deity. Again, I found it stretched on longer than necessary. Like Job, our Pi has to go through numerous challenges to test his faith.

The book opens with the artifice of the author (Yann Martel) telling the (fabricated) story about how he came to write the book. This is an old trick, used by many authors – Edgar Rice Burroughs used it to open several of his tales, William Goldman uses it in The Princess Bride, for example. But where Martel retires his character early in the book (before the shipwreck, other than a small aside near the end), film director Ang Lee drags him into the story right until the very end, which I found a little more intrusive.

The book opens with the artifice of the author (Yann Martel) telling the (fabricated) story about how he came to write the book. This is an old trick, used by many authors – Edgar Rice Burroughs used it to open several of his tales, William Goldman uses it in The Princess Bride, for example. But where Martel retires his character early in the book (before the shipwreck, other than a small aside near the end), film director Ang Lee drags him into the story right until the very end, which I found a little more intrusive.

The opening is a lengthy set up to explain how and why Pi Patel finds himself along on a lifeboat, drifting across the Pacific Ocean in the company of a Bengal tiger. It’s also used to explain how Pi grows up trying to wrestle with faith, losing it in the institutionalized form, and finding it internally. A lot of this is glossed over or condensed in the film. However, there’s a family dinner conversation in the film where the father urges the son to use reason instead of blind faith that isn’t in the book. To me, that was an important counterpoint to Pi’s searching, but it never comes back.

The book and the movie end (spoiler alert) differently, but not dramatically so. Lee brings the author back into the story to help explain things, where Martel has left himself in the early third of the novel. Both include the rather curious – and contrived – hospital interview between Pi and the Japanese transportation officials about the sinking.

This is where the relativity of truth comes into play. The officials reject Pi’s story about the tiger, and ask for another one, which he duly gives; one in which crew mates and his mother survive, not zoo animals. Pi asks which story they prefer. The book has stories within stories within stories.

Here faith, belief, truth and fantasy all collide. But to me, that was a little too much like the audience asking the magician to explain his tricks, peeking at the man behind the curtain. It felt clumsy. I wanted to be left wondering, but instead was treated to a lecture on allegory. The author makes you step outside the tale.

Were his animals mere metaphors for human companions? You are left to wonder if the officials preferred Pi’s tale not because (or whether) it was true, but rather that the alternative – of human cruelty, murder and cannibalism – was too gory for the squeamish bureaucrats.

Is Martel trying to lecture us on the variable nature of truth? Or commenting on faith itself: believe the fantasy because reality is not for the squeamish?

The bulk of the book and film between the sinking and the Mexican hospital is a Captain Bligh-like tale of survival at sea. The reader is set up for this in the book by the casual mention of Robinson Crusoe on his mother’s bookshelf, but it’s not obvious until later that was the author’s nudge and wink.

It’s actually a well-thought-out adventure of survival, cunning, and maturity. Lee’s Pi drifts less into the madness of isolation and hunger than Martel’s, and we are spared some of the lengthy talks with himself. Lee’s imagery is gorgeous, and evocative in places where Martel’s descriptions are somewhat dry. You want to keep watching for the sheer beauty of the film.

The movie is fairly true to the book, given the odd setting. Lee does drop some material, including what to me were two important scenes: one where the Christian priest, Hindu pandit and Muslim iman discover Pi has been pursing all three religions and they confront him and one another over who he has to follow. This, to me, was a comment on the inflexibility (and dangers) of institutionalized religion.

The other dropped scene is where Pi meets another castaway mid-ocean. That shows how thin the patina of humanity is, how easily it wears through to the beast underneath when we’re in extreme situations. This darker stuff is left out of the movie.

In the end, though, what’s the message? Does Pi’s faith survive intact? Does he decide to choose one of the three religions (as his parents and the religious leaders urged earlier)? Does he give up on religion and, like his father urged, turn to reason? Does he reject his god(s) or like Job accept the ineffable nature of his deity? We never really know.

It’s suggested in the introduction that the story will make the author “believe in God” but I don’t think it does. It might make him believe in the resiliency, the courage and the resourcefulness of the human spirit in adversity, but not necessarily in the supernatural.

In the film, there are no obvious religious icons or images in his house, seen when the writer interviews him. He doesn’t talk about faith with the author. The story lacks completion in a part that was carefully built up in so much of the early part of the book. We get to know how Job decides, why not Pi? The confusion about faith that starts the film remains with us at the end.

It’s a visually stunning film, and worth watching, but not entirely satisfying in its ending or message.

You say:

“In the end, though, what’s the message? Does Pi’s faith survive intact? Does he decide to choose one of the three religions (as his parents and the religious leaders urged earlier)? Does he give up on religion and, like his father urged, turn to reason? Does he reject his god(s) or like Job accept the ineffable nature of his deity? We never really know.”

I would argue that we do know. I think the point is made when Pi is interviewed by the Japanese incident inspectors regarding the sinking. He provides two alternative stories. The (arguably) true version is the one where the human survivors fight among themselves. There is murder and canabalism. The (arguably) invented story is the one where Pi survives at sea with the Bengal tiger (and other animals representing the human survivors of the actual wreck). The outcome of each story is essentially the same: the ship is lost, Pi doesn’t really know why, and he is the only survivor. The wise inspectors thus choose the version they prefer; the second.

I think the book and film apply this reasoning to organised religion. It doesn’t matter which story you prefer; Christianity, Islam, Judaism. They are likely all technically incorrect human inventions. However, the result is the same; there is one God, one creator. This explains why Pi appears to embrace all religions equally. He can’t possibly believe the details of each, but he is clearly a spiritual person.

You say:

“In the end, though, what’s the message? Does Pi’s faith survive intact? Does he decide to choose one of the three religions (as his parents and the religious leaders urged earlier)? Does he give up on religion and, like his father urged, turn to reason? Does he reject his god(s) or like Job accept the ineffable nature of his deity? We never really know.”

I would argue that we do know. I think the point is made when Pi is interviewed by the Japanese incident inspectors regarding the sinking. He provides two alternative stories. The (arguably) true version is the one where the human survivors fight among themselves. There is murder and canabalism. The (arguably) invented story is the one where Pi survives at sea with the Bengal tiger (and other animals representing the human survivors of the actual wreck). The outcome of each story is essentially the same: the ship is lost, Pi doesn’t really know why, and he is the only survivor. The wise inspectors thus choose the version they prefer; the second.

I think the book and film apply this reasoning to organised religion. It doesn’t matter which story you prefer; Christianity, Islam, Judaism. They are likely all technically incorrect human inventions. However, the result is the same; there is one God, one creator. This explains why Pi appears to embrace all religions equally. He can’t possibly believe the details of each, but he is clearly a spiritual person.

You say:

“In the end, though, what’s the message? Does Pi’s faith survive intact? Does he decide to choose one of the three religions (as his parents and the religious leaders urged earlier)? Does he give up on religion and, like his father urged, turn to reason? Does he reject his god(s) or like Job accept the ineffable nature of his deity? We never really know.”

I would argue that we do know. I think the point is made when Pi is interviewed by the Japanese incident inspectors regarding the sinking. He provides two alternative stories. The (arguably) true version is the one where the human survivors fight among themselves. There is murder and canabalism. The (arguably) invented story is the one where Pi survives at sea with the Bengal tiger (and other animals representing the human survivors of the actual wreck). The outcome of each story is essentially the same: the ship is lost, Pi doesn’t really know why, and he is the only survivor. The wise inspectors thus choose the version they prefer; the second.

I think the book and film apply this reasoning to organised religion. It doesn’t matter which story you prefer; Christianity, Islam, Judaism. They are likely all technically incorrect human inventions. However, the result is the same; there is one God, one creator. This explains why Pi appears to embrace all religions equally. He can’t possibly believe the details of each, but he is clearly a spiritual person.