![]()

In the late 1950s, I came across a copy (1912; an original edition, I believe) of Edgar Rice Burrough’s first published novel, Tarzan, The Ape Man, on my parent’s bookshelf in the basement. A forgotten book, one my father had likely brought with him from England when he immigrated here in 1947, something from his own boyhood. It sat beside old volumes of the Boy’s Own Annual and other English books. Of course I had to open it and read it.

In the late 1950s, I came across a copy (1912; an original edition, I believe) of Edgar Rice Burrough’s first published novel, Tarzan, The Ape Man, on my parent’s bookshelf in the basement. A forgotten book, one my father had likely brought with him from England when he immigrated here in 1947, something from his own boyhood. It sat beside old volumes of the Boy’s Own Annual and other English books. Of course I had to open it and read it.

From the very start, I was fascinated by it, by the adventure, by the sheer fantasy of it all. It was, as I recall more than 50 years later, the first ‘adult’ novel I ever read.* It was also the only such book on the shelf – among the various textbooks, Agatha Christie mysteries, and a few odds end ends. Only Tarzan, among them, held my attention.

In the early 1960s, I discovered science fiction. I used to wait in the local library for my father to pick me up after work (my mother was in hospital for a couple of years), and the library was a safe, welcoming place, albeit the Bendale branch was small. I was precocious and bored; and the children’s section was too small to contain my restless intelligence. I soon graduated from the children’s section to adult books in my impatience. I read voraciously.

Top of the list of fiction I read then were novels by writers like Andre Norton, Ben Bova, Chad Oliver, Isaac Asimov, Ray Bradbury, Arthur C Clarke, Theodore Sturgeon, L. Sprague de Camp, Robert Heinlein, John Wyndham, James Blish, John W. Campbell, Fritz Leiber, Poul Anderson, Philip K. Dick, Frank Herbert, Lester del Rey, Jack Vance, Brian W. Aldiss and many others. By the time I reached my teens I had read hundreds of scifi and fantasy novels. A lot of ‘space opera’ among them.**

About the same time, in the early half of the 1960s, paperback publishers like Bantam and Ace started reprinting the pulp stories of the pre-war years. While some kids collected baseball and hockey cards, I collected paperback book series.

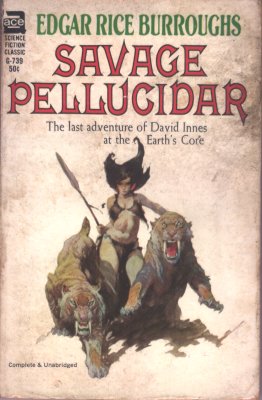

Soon all of the works of Edgar Rice Burroughs were available in print, and I bought every one, building a library of his works (which I still have, mostly complete, although I may be missing a few of his western titles). I avidly read his Barsoom and Pellucidar series, finding them far more entertaining than the many Tarzan novels (which I collected and read, anyway). Given that the first Barsoom novel was written in 1912, it certainly has had staying power.

A few years ago, I bought a commemorative edition that had the three Caspak novels: The Land That Time Forgot, The People That Time Forgot and Out of Time’s Abyss. Great, ripping adventure. Dated, of course, but still highly readable and some of Burroughs’ best writing. I still reread his stuff, a couple of times a year, but not with the same fervour I did when I was buying the paperbacks from my meagre allowance.

Robert Howard, the creator of Conan, Kane, and others, was another author whose fantasy adventures were reprinted then. Howard was probably the best writer of the lot, and his prose is still very readable, and not as formulaistic as Burroughs. Howard’s characters are far more realistic and multi-dimensional than many of his contemporaries. Howard’s writing career was all too short, ending with his suicide at the age of 30. Had he lived, I’m sure he had true greatness in him.

In 2010, Prion Books released a compendium of Howard’s Conan tales, including Red Nails, Jewels of Gwahlur, The Devil in Iron and six others in a 500-plus page book. I managed to find a copy recently at Cover-to-Cover books, here in Collingwood, a few weeks back, and am working my way through it now (reading it prompted me to write this piece). Sadly, I have only a couple of the Howard paperbacks from the 60s in my collection (both in rather sorry shape).

Both Howard’s and Burroughs’ reputations have suffered from generally execrable movies about their characters. Conan – Howard’s greatest character – became a caricature played by Arnold Schwarzenegger. Although his Conan films are entertaining, they are not close to Howard’s gritty, imaginary worlds. The 2011 version of Conan was a lot more like Howard’s environment, but the film was spoiled by cardboard characters and wooden dialogue. The awful 2008 film, 10,000 BC, was, I believe, inspired by Howard’s writing, but it too failed to develop believable characters (it’s been sarcastically renamed “Stargate: The Early Years” by some scifi buffs).

Tarzan films have been made since 1918 (the first full-length talkie was released in 1932) – 48 until 2005. Most are entertaining, but not Burroughs. In fairness, the 1984 movie, Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes, was a good attempt to capture the Burroughs story and ambiance and it was certainly closer to the original than any of the Johnny Weissmuller or Gordon Scott films.

In the 2012 flick, John Carter of Mars (which really should have been titled A Princess of Mars, like the book was), Disney sanitized the semi-raunchy Burroughs by clothing his naked heroes and heroines, and dulled the story down to a CGI sitzkrieg with a Martian calot turned into semi-dog/semi-lizard for comic relief (or as this site calls it, a cross between Jabba the Hutt and a squirrel). Spectacular, action-packed, and entirely forgettable.

Peter Bradshaw, a reviewer in The Guardian wrote of it:

John Carter is one of those films that is so stultifying, so oppressive and so mysteriously and interminably long that I felt as if someone had dragged me into the kitchen of my local Greggs, and was baking my head into the centre of a colossal cube of white bread. As the film went on, the loaf around my skull grew to the size of a basketball, and then a coffee table, and then an Audi.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tdg0uipoCUI]

The only other film based on the Mars series was a 2009 direct-to-DVD disaster, Princess of Mars, co-starring Traci Lords.

[youtube=www.youtube.com/watch?v=YO5RC-qeGqY]

Perhaps it’s best that no one else has attempted to translate Burrough’s Barsoom onto film. Film simply pales when compared to human imagination when evoked by reading.

Doc Savage novels were among the reprints. The series was created by several people, and has no one author, but I’ve read that 67 of the tales were reprinted in the 1960s. I can’t recall how many I had, but at least two dozen of them. This list suggests 181 titles in the series, total. Two Doc Savage movies were made, both disasters.

Another novel that resurfaced in the mid-1960s was William Hope Hodgson’s gothic House on the Borderland, an odd, Lovecraftian-style horror that has since slipped into the public domain and can be downloaded online or as an audio book.

These writers were my favourite reads, along with other science fiction authors. They encouraged me to write for myself – crafting stories often based on their characters. I never really mastered the art of fiction, but it’s great fun to attempt. I’ve always suspected that, had I lived between the wars, I would have joined the ranks of the pulp writers.

~~~~~

* The first adult non-fiction was The Life of the Spider, by the 19th century naturalist, J. Henri Fabre. I read it while in bed with some childhood illness, around age 10 or 11. Somewhere around the age of 12, I read Darwin’s Origin of Species, too. Both deserve a second reading – Darwin in particular.

** In 1965, I found Dune, Frank Herbert’s scifi masterpiece, in the local library-mobile that services our corner of Scarborough. I have owned perhaps a dozen copies – most given away to friends – and read it at least four times I can recall, and will likely read it at least once more in the next year or two. I didn’t discover Tolkein until 1968.