You probably entered local politics for some or all of the same reasons the rest of us did: to make a difference. We put our names forward because we wanted to change the way things are, we wanted to fix problems, to change the old mindsets, to move forward, to heal wounds, to contribute to our communities, to work towards a greater goal and to do good and even great things.

We entered politics for noble and lofty reasons. We had dreams, goals, plans and designs to build a better community.

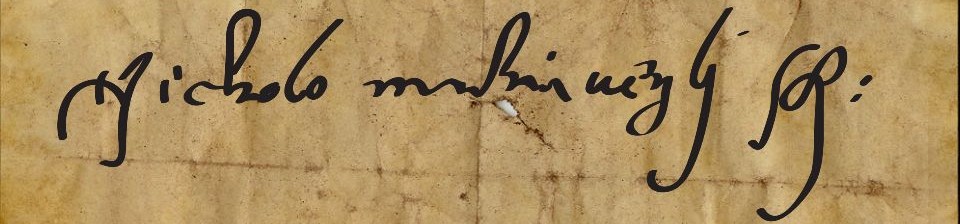

“It is a strange desire, to seek power over others, and to lose your power over a man’s self. The rising into place is laborious, and by pains men come to greater pains; and it is sometimes base; and by indignities men come to dignities.”

Francis Bacon: Essays – Of Great Place

You did not intend to get into fights with fellow councillors, to confront staff, conspire to defeat other members’ initiatives, lobby in back rooms, form cliques, build a secret power base among staff and board members, to shout down another member at the table, or shoulder your way to the front of the line during the photo op.

But you did.

Well, most of us have done so. You didn’t do any of these things if you were happy to be dominated by councillors with a stronger will, you didn’t care about your reputation, were willing to fall in front of the bus for staff, or were simply hopelessly naïve.

Surprisingly, even if you didn’t play the power games, even if you didn’t race to get the media attention or staff support before anyone else, even if you didn’t twist arms in the back rooms to get your vote passed, you may still be popular, respected and get re-elected. It happens. It’s like the lottery: someone, after all, wins.

Just not the majority of us.

Municipal politicians should appreciate Machiavelli. He understood that we have to make decisions that ordinary citizens never have to. He examined the far-reaching consequences of our decisions on both our communities and on ourselves. He said that politicians must do what is necessary, not simply what we want to do, but we should be aware of the cost of our choices, both in the present and for the future of our municipality.

Machiavelli is, however, for more than politicians. His rules and insights can be applied to almost formal organization: they work as well for any board and committee, or corporate management and executive hierarchies.

Although reviled by his critics as an amoral political philosopher, Machiavelli had a strong sense of ethics and morality, bound up in his understanding of honour mixed with responsibility. However, he understood that the ruler was not bound by the same rules of morality that regular citizens lived by, and that rulers were often torn by having to choose between morality and expediency.

Rulers make choices, rulers take risks. You learn this in your first term in office.

He recognized that leaders bear a burden of responsibility for the difficult choices they make, and risks they take – a sometimes terrible burden. But adversity helps create stronger leaders, too.

Doing What is Necessary

Machiavelli wrote that strong measures in the short term might be necessary even by the kindest of rulers, in order to achieve a longer term goal. Any politician wrestling with a municipal budget to both preserve services and keep taxes low will appreciate this.

He also understood that those harsh measures are unpopular and ultimately unsuccessful if continued over the longer term. Many a democratic government has been voted out of office for continued harsh measures like escalating taxes and user fees paired with reduced services.

Machiavelli understood, too, that the populace often viewed the barons and nobles – today’s municipal staff or political appointees – with suspicion, jealousy and even hatred. He counselled politicians that, if they had to choose between loyalty to the electorate or their nobles, to choose the electorate. It is popular belief, he wrote, that,

“All who attain great power and riches, make use of either force or fraud; and what they have acquired either by deceit or violence, in order to conceal the disgraceful methods of attainment, they endeavor to sanctify with the false title of honest gains.”

The Florentine Histories: III, 3

This focus on staying in power wasn’t entirely selfish: Machiavelli tied the welfare of the people and the state to the behaviour of the ruler. The better ruler’s actions directly define the happiness of the people. Machiavelli stressed that the ruler built his or her state on the goodwill of its people, not on personal glory or acquisitions.

Duty to the whole state is, for Machiavelli, the ultimate, noble cause for the ruler. The ruler, he wrote, has the responsibility to protect the state, not simply guard his own power.

The state needs to be whole to be successful. Turmoil divides a state, and a divided state leads to more trouble. Keeping order, and preventing turmoil and disruption, often means stifling opposition and dissent.

He had no patience for dithering or a ‘middle road’ approach – he promoted swift, decisive action when confronted with a challenge, and taking sides.

Throughout his works, Machiavelli showed respect for those who achieved greatness through talent, brains and ability – that elusive term, virtu. He had little respect for those who relied on fate or chance, but respected those who used fate to their own ends.

Machiavelli was, above all, a pragmatist.

While rulers walk a fine line between being good and cruel, between being loved and feared, he always expected them to make the choices that benefited the state first, and their own interests second.

In the end, municipal politicians will be judged like his rulers: by the good they do for their municipality. The benefit to the state is the ultimate measuring stick. If everything you do is simply to further your own glory, you are destined to fail.

In today’s climate of political correctness, his bluntness may seem amoral, but it would be hypocritical of any politician not to acknowledge his truths and admire his candor.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Previous Chapter – Next Chapter

- Machiavelli and Sejanus - October 14, 2022

- A Meeting of the Minds? - July 3, 2021

- Machiavelli’s Prince as satire - June 8, 2017