Is Machiavelli still relevant in the post-truth era? Can he help us understand the rise of modern demagogues like Donald Trump? I believe so, but in great part it depends on the translation.

Is Machiavelli still relevant in the post-truth era? Can he help us understand the rise of modern demagogues like Donald Trump? I believe so, but in great part it depends on the translation.

Many readers were introduced to Machiavelli’s masterwork, Il Principe, through the translations of late 19th and early 20th century editors like William Kenaz Marriott. Thanks to the lapse of copyright, the 1908 Marriott translation is easily the most commonly version reprinted today and most discount editions are simply reprints of his work. Some are a bit rough because they’ve been ported from paper to digital format and back to paper without careful proofreading.

Some are the result of OCR (optical character recognition) scanning of an old text. When OCR works well, it’s a great, time-saving tool. But in my own experience, a murky or aged text can baffle the software: is it an “o” with a broken or faint right side? A “c”? An “e”? A “d” missing the stem? Scanned text requires a keen editorial eye to find these errors, and that’s not always provided in public domain editions.

Not that Marriott’s version is per se wrong: merely outdated and somewhat florid by today’s literary standards. The same is true of the Dacres version – translated in 1640 – and the Neville version – translated 1675 – both of which can also be found among the public domain editions. Purple prose from any era can distract the modern reader from the message. Like the King James Bible versus, say, a modern translation, it can feel archaic, stuffy, formal. That can dilute the relevance of Machiavelli – and his punchy practicality – to modern politics.

Some subsequent editors appear to have used Marriott as the base for their own later translations. Most of the editions I’ve read have been crafted by academics rather than politicians or historians who might have a better grasp on the implementation, not just Machiavelli’s theory.

Some translators focus on the individual words or grammar, rather than the overall sense and the message within them. The results may be technically or linguistically correct, even paralleling Machiavelli’s own style, but often come across as stilted and fusty as Marriott.

Of course, it isn’t always easy to make a 16th century work (and an early 16th century one, at that) read like a modern book. It’s not simply the language that has changed, but the cultures, technologies, religions, social interactions and attitudes, foods, clothing… pretty much everything. To make the ideas and the words relevant to modern readers, a translator must present them in ways that not only make sense to us today, but provide a comfortable read that doesn’t have us always hunting end- or footnotes to clarify a phrase or word.

And no translation is ever perfect: each one will be spiced by the translator’s own views, background, understanding, opinions and education. A translation is always an interpretation. You need to choose one that speaks to you in a meaningful way.

Continue reading “Tim Parks translates The Prince”

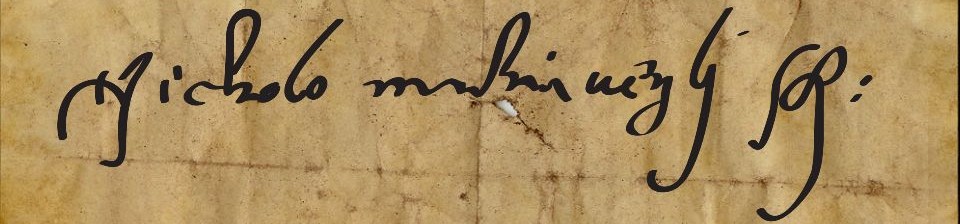

Niccolò Machiavelli only mentions Lucius Aelius Sejanus (aka Sejanus; 20 BCE – CE 31) once in his works: in a single paragraph found in his Discourses, Book III, Chapter VI—Of Conspiracies. Even then, Machiavelli only mentions him in passing in a very short list of conspirators (trans. Marriott, emphasis added):

Niccolò Machiavelli only mentions Lucius Aelius Sejanus (aka Sejanus; 20 BCE – CE 31) once in his works: in a single paragraph found in his Discourses, Book III, Chapter VI—Of Conspiracies. Even then, Machiavelli only mentions him in passing in a very short list of conspirators (trans. Marriott, emphasis added):

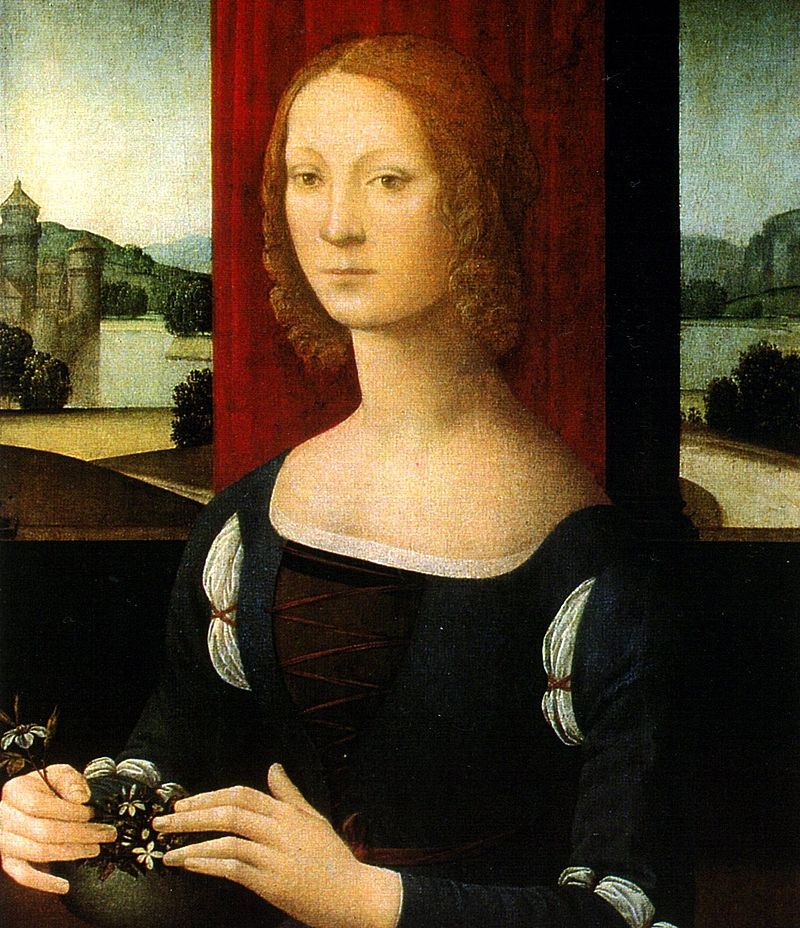

Niccolo Machiavelli and Michel de Montaigne never met, nor could they have — Machiavelli died six years before Montaigne was born, and they lived about 1,200 km (800 miles) apart — but imagine the conversations they could have had if they had lived at the same time and close enough to visit one another, to have dinner together.

Niccolo Machiavelli and Michel de Montaigne never met, nor could they have — Machiavelli died six years before Montaigne was born, and they lived about 1,200 km (800 miles) apart — but imagine the conversations they could have had if they had lived at the same time and close enough to visit one another, to have dinner together. There are scholars and readers who have suggested Machiavelli wrote The Prince as a satire, along the lines of Jonathan Swift’s A Modest Proposal. That he was pointing out how leaders should not behave, a sort of tongue-in-cheek work.

There are scholars and readers who have suggested Machiavelli wrote The Prince as a satire, along the lines of Jonathan Swift’s A Modest Proposal. That he was pointing out how leaders should not behave, a sort of tongue-in-cheek work.

Whilst perusing the Net for some material for my book on Machiavelli, some time back, I came across this maxim: “Never attempt to win by force what can be won by deception.”

Whilst perusing the Net for some material for my book on Machiavelli, some time back, I came across this maxim: “Never attempt to win by force what can be won by deception.”