![]()

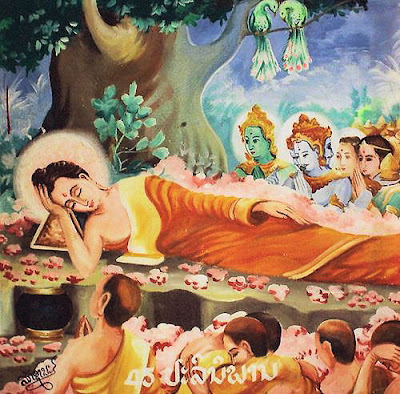

Buddha’s death considered as we approach Vesak

Shakyamuni died from eating tainted pork accidentally offered to him by a well-meaning lay devotee…. that story permeates Buddhist history and mythology, and has spawned many debates both about both his death and the morality of eating animal flesh. Okay, it wasn’t necessarily bacon…

Shakyamuni died from eating tainted pork accidentally offered to him by a well-meaning lay devotee…. that story permeates Buddhist history and mythology, and has spawned many debates both about both his death and the morality of eating animal flesh. Okay, it wasn’t necessarily bacon…

This story is mentioned in the book, Faces of Compassion: Classic Bodhisattva Archetypes and Their Modern Expression, as well as on many online sites. Generally, the Western Buddhist sources I read accept it as factual and some take it as permission for Buddhists to eat meat.

But is it history? or is it a morality tale, meant to instruct rather than to be taken as fact? Or is there something else in it?

On the Fraught With Peril blog, it offers some insight into the challenges – and subtleties – of interpreting the tale. The meal contained something called…

…sukara-maddava, which can be translated as either “soft pork” or as “pig’s delight.” No one knows for sure what this was. It might have been pork, because the Buddha allowed monastics to accept meat as long as it was not seen, heard, nor suspected that an animal had been killed for their sake. On the other hand, it might have been a type of mushroom that pig’s also liked to eat. In any case, the Buddha tried some of this and sensed that something was wrong.

The ‘something’ that was wrong was happening inside his gut. Here’s where the modern twist enters the story. Modern doctors, reading the stories, have applied their diagnostic skills and come up with an alternative to food poisoning:

Dr. Mettanando Bhikkhu has argued that it was not food poisoning after all, but rather a condition known as mesenteric infarction that was what killed the Buddha. As mentioned before, this is a condition brought on by old age in which the artery that supplies blood to the small intestines is blocked. This causes an infarction or gangrene of the intestinal wall or mesentery. Mesenteric infarction is fatal if untreated by surgery. The Buddha’s severe abdominal pains or angina during the rainy season retreat in Beluva signaled the onset of this condition. During his meal at the home of Chunda the Buddha suffered a second angina attack and at first thought the sukara-maddava was responsible. Food poisoning, however, would not be felt until at least a couple of hours after the meal and not immediately. After the meal was finished the Buddha gave a Dharma talk to his host and then took his leave. That is when other more severe symptoms occurred, and the Buddha realized that this was no mere food poisoning.

So it might not have been the food itself, but simply the Buddha’s age (he was 80 at the time), that caused the problem. Age, however inevitable, doesn’t make much of a morality lesson.

The Manitoba Buddhist Temple offers this curious spin on the story; it suggests conspiracy or subterfuge by competing religious schools or teachers who resented the Buddha’s large and growing following. And possibly murder?

The Manitoba Buddhist Temple offers this curious spin on the story; it suggests conspiracy or subterfuge by competing religious schools or teachers who resented the Buddha’s large and growing following. And possibly murder?

…Shakyamuni was poisoned to death when tainted pork was dropped into his begging bowl by a resentful Brahmin.

There was likely the same sort of theological infighting and jealousies in Buddhas’ time as have plagued religious since they were first invented. Did Brahmins attempt to crush the movement (itself a subject of much debate and discussion online)? Or was a plot hatched by his former disciple, Devadatta, in league with Prince Ajatasattu? Interesting stuff, but the facts are lost in time and shrouded in myth; and well beyond the scope of this post.

The opposite side of this coin is the idea the Buddha knew the meat/mushroom was spoiled but ate it anyway, in a self-sacrifice, a lesson for his followers that would be paralleled in Jesus’s death, more than half-a-millennium later. The Manitoba temple blog later explains:

Many elements of this conflict still exist in India today. The Brahmins emphasized that vegetarianism was spiritually superior to meat eating. Those who ate meat were seen as socially and religiously inferior. This created an indelible line that still runs through Asian society today. Shakyamuni would eat meat, however, if it had not been specially prepared for him and if it were placed in his begging bowl as an offering. This was his way of expressing solidarity with those being rapidly displaced and relegated to lower classes. He was also questioning the mere outward show of religion.

Wikipedia gives this version of the tale, which suggest Buddha was aware of his impending death and was prepared for it:

According to the Mahaparinibbana Sutta of the Pali canon, at the age of 80, the Buddha announced that he would soon reach Parinirvana, or the final deathless state, and abandon his earthly body. After this, the Buddha ate his last meal, which he had received as an offering from a blacksmith named Cunda. Falling violently ill, Buddha instructed his attendant ?nanda to convince Cunda that the meal eaten at his place had nothing to do with his passing and that his meal would be a source of the greatest merit as it provided the last meal for a Buddha. Mettanando and Von Hinüber argue that the Buddha died of mesenteric infarction, a symptom of old age, rather than food poisoning.

Sunyananda Dharma, who blogs under the name, The Errant Abbott, wrote:

Buddha Shakyamuni himself died of eating tainted pork that was offered to him in alms, whereas modern day luminaries of the dharma, such as HH Dalai Lama, staunchly abstain from animal products.

The great translator, Arthur Waley wrote about why this story has such an impact, even today:

Anyone who is known to take an interest in the history of Buddhism is bound to be asked from time to time whether it is true that Buddha died of eating pork. The idea that he should have done so comes as a surprise to most Europeans; for we are in the habit of regarding vegetarianism as an intrinsic part of Buddhism. Enquirers with an iconoclastic bend of mind are anxious to have it confirmed that Buddha was something quite different from the conventional holy man; something robuster, yet at the same time less pretentious; while those who have treasured the figure of Gautama the Saint, immune from every worldly appetite or desire, are eager to secure authority for a figurative interpretation of the pork-eating passage.

To clarify, calling it pork is an interpretation of a rare Sanskrit word, translated from a long-unspoken language into English – but its exact definition is still disputed among Sanskrit and Buddhist scholars. It may in fact simply be a bad translation of an uncommon word, but the choice of translation has significant impact.

The reference to the Buddha’s last meal comes from the Mahaparinibana Sutra, an early Theravadin work written in Sanskrit. In this work, the food prepared for that meal is called “suukaramaddava,” a word that appears nowhere else in the sutras.

Arthur Waley continued on this word and its meaning in his 1932 essay, “Did Buddha die of eating pork?” Waley noted that… (emphasis added):

The word suukaramaddava occurs nowhere else (except in discussions of this passage) and the -maddava part is capable of at least four interpretations.

Granting that it comes from the root MRD ‘soft’, cognate with Latin mollis, it is still ambiguous, for it may either mean ‘the soft parts of a pig‘ or ‘pig’s soft-food‘ i.e. food eaten by pigs.

But it may again come from the same root as our word ‘mill’ and mean’pig-pounded‘, i.e. ‘trampled by pigs’.

There is yet another similar root meaning ‘to be pleased’, and as will be seen below one scholar has supposed the existence of a vegetable called ‘pig’s-delight’.

So the Buddha may not have eaten pork, but rather food prepared for pigs, enjoyed by pigs (like truffles), or food milled by pigs. That’s a wide range of alternate meanings. All of which certainly change the story for those Buddhists who use it to justify eating animals.

Waley also lists several medicinal plants listed in contemporary works that include the prefix “pig” in them – suukara-kanda (pig-bulb), suukara-paadika (pig’s foot), sukaresh.ta (sought-out by pigs).

Waley also lists several medicinal plants listed in contemporary works that include the prefix “pig” in them – suukara-kanda (pig-bulb), suukara-paadika (pig’s foot), sukaresh.ta (sought-out by pigs).

Another translator, Neumann, takes suukaramaddava to mean ‘pig’s delight,’ a kind of truffle. So there is a valid argument to be made that the word does not mean pork, but rather a plant that has a relationship with pigs.

Waley doesn’t discount the possibility the word meant pork – the sutra is unclear – but indicates strongly that it could have had other meanings. That rings true when one considers that a lay believer would be unlikely to offer the Buddha a meat dish, given that the Buddha taught the principle of non-harm (ahimsa, see below) to all living creatures from the very earliest days.

The significance of a single word to the later doctrine cannot be overlooked, however. Taken one way, it allows Buddhists leeway to eat meat (Shakyamuni leading by example: if the Buddha did it, it must be right), regardless of some contradictions to this in other texts. Taken another, it fortifies the argument for vegetarianism in Buddhism.

Fifth century Chinese translations of the sutras (and the subsequent canon in Chinese) do not include the “death by pork” comment, but instead indicate the last meal was a vegetarian dish that included a fungus grown on a sandalwood tree (rather than meat). Similar, I suppose, to truffles.

The early Mahayana texts had strict prohibitions against eating flesh and that has continued to be part of the main Mahayana practice since the line was founded. The first Mahayana reference to a meatless diet is found in the Mahaaparinirvaana Sutra. However, these prohibitions are not found in the earlier Theravadin works, which can claim doctrinal precedence.*

Hence the millennia-old argument about whether vegetarianism is doctrine, or optional, in Buddhism. It depends in part on whether you belong to a Theravadin or Mahayanin school. But the practice of vegetarianism has not been strictly applied in Mahayana schools, and some Theravadin schools have taken it up as accepted practice. The lines are blurred.

Waley makes an educated guess that vegetarianism arose among Hindu followers of Vishnu a century or two before the Mahayana movement took root (the Vishnu cult was the rising movement in Hindu culture at that time). Cultural and social pressures from the Hindu majority may have pushed the minority Buddhists to accepting their neighbours’ vegetarian lifestyle in order to reduce friction in their communities. This became doctrinal when the Mahayana texts were being written, somewhat later – revisionism, one might call it. Perhaps, but that doesn’t explain Buddha’s express doctrine of ahimsa (see below) right from his earliest days.

Whether or not the Buddha died from eating pork or truffles is an interesting philological discussion, but not the real question, however. It is whether Buddhists today can morally justify killing other beings for convenience, pleasure, sport or comfort. Should Buddhists accept the moral responsibility of finding compassionate solutions, even if they are inconvenient?

As the Jade Turtle site notes,

“…ahimsa (non-harming towards all living beings) is a basic tenet and also the basis for the very first precept of Buddhism.”

Can one ever justify inflicting pain, torture, brutality and violence – violent and agonizingly painful death – on another creature? Especially on another sentient being who is screaming and writhing in pain? If you say no, then you cannot in any conscience eat meat. Ahimsa: compassion, harmlessness.

But if it is not a factual story, and it’s not about meat, what is the morality behind the tale? First that Buddha knew of his approaching death (Parinirvana – a day celebrated by Buddhists) and prepared for it – and prepared his followers for it – with calm grace and dignity. Second that, he absolved Chunda from any blame because Shakyamuni knew what he was doing and accepted the consequences of his own actions:

On the day before his passing, the Buddha was offered a meal from Chunda, a pious metalsmith. The Buddha accepted the meal offering, but instructed that nobody else should partake of it because the food was contaminated. The food caused the Buddha to become fatally ill, and Chunda was overcome with guilt and remorse when he learned that his offering would probably lead to the Buddha’s demise. The Buddha consoled him by saying that the one who offers the Buddha’s last meal acquires great merit that is equal to the merit from an offering made to the Buddha right before his attainment of Enlightenment…

The reason why he accepted it then was because, firstly, he did not wish to deny anyone the merit of making an offering to the Buddha; and secondly, he was already eighty years old at the time and he wanted to show as a lesson to everyone that all living beings without exception are susceptible to impermanence and death.

it’s about mortality, responsibility, and blame. Practicing Buddhism means taking responsibility for one’s actions. According to legend, Buddha’s last words** were,

All conditioned things are of transient nature; Strive on untiringly, with diligence.

~~~~~

* Actually there are quite a few prohibitions on eating meat in the sutras and in later Buddhist discourses, all written centuries before anyone ever conceived of animal rights. There is a particularly important passage in the Lankavatara Sutra in which the Buddha tells his followers why he will not permit them to eat flesh. Here’s an excerpt:

Thus, Mahamati, wherever there is the evolution of living beings, let people cherish the thought of kinship with them, and, thinking that all beings are to be loved as if they were an only child, let them refrain from eating meat. So with Bodhisattvas whose nature is compassion, [the eating of meat] is to be avoided by him. Even in exceptional cases, it is not [compassionate] of a Bodhisattva of good standing to eat meat. The flesh of a dog, an ass, a buffalo, a horse, a bull or a man, or any other being, Mahamati, that is not generally eaten by people, is sold on the roadside as mutton for the sake of money; and therefore, Mahamati, the Bodhisattva should not eat meat…

All meat-eating in any form, in any manner, and in any place, is unconditionally and once for all, prohibited for all…

Thus, Mahamati, meat-eating I have not permitted to anyone, I do not permit, I will not permit.

There is also a passage in the Brahmajala Sutra which states:

Pray let us not eat any flesh or meat whatsoever coming from living beings. Anyone who eats flesh is cutting himself off from the great seed of his own merciful and compassionate nature, for which all sentient beings will reject him and flee from him when they see him acting so. . . Someone who eats flesh is defiling himself beyond measure…

From the Surangama Sutra:

If a man can (control) his body and mind and thereby refrains from eating animal flesh and wearing animal products, I say he will really be liberated.”

And from the The Mahaparinirvana Sutra:

The eating of meat extinguishes the seed of great Compassion.

Most of the prohibitions against meat are from the Mahayana texts and traditions, but there are a few to be found in earlier works as well.

Yes, you can find contradictory quotes too – but the Buddha was clear that his followers should not cause any animal to be killed for himself. When he accepted meat as alms, Buddha spoke about the sort of meat permitted (Meat ordered or received by mistake; Leftover or discarded meat; Meat from animals that have died naturally or by accident for at least 16 hours (to ensure consciousness has left the body), and Meat donated as alms collected during the begging rounds).

You can find other quotes about refraining from meat from traditional Buddhist texts online, including some quotes about eating meat from the Dalai Lama and contemporary teachers at Buddhist Quotations and Buddhist Vegetarian Quotations.

In several works, the Buddha encouraged his followers to develop loving-kindness (metta), compassion (karuna), sympathetic joy (mudita), and equanimity (upekkha) to all creatures. And, of course, ahimsa. Not just for humans: for all beings.

But eating meat isn’t the real issue here: it’s the application of a fundamental, ethical responsibility: compassion. In The Great Compassion: Buddhism & Animal Rights, Norm Phelps wrote:

The beginning of mindful eating is the realization that eating meat is not about the meat-eater; it is about the animals who are tormented and killed.”

So can someone be a Buddhist if his or her compassion stops short of inconveniencing self-interest and personal comfort? Buddhism is about awareness (mindfulness), taking responsibility, and compassion. Anyone who practices these three, anyone who applies them daily, understands the choices we make, and the consequences. If you truly believe yourself a Buddhist, you sometimes have to make choices that are difficult, but that benefit other living beings. Eating meat from factory farms violates every Buddhist precept and law I know.

Buddhism isn’t the only religion with compassion. However, Buddhists are expected to practice it in daily life, and hold it above their own personal needs fulfillment, which seems unique.

A practicing Buddhist should not make choices simply out of personal convenience, personal comfort, ease of shopping or dining, or by laziness, disinterest or lack of compassion. Every thing you do, every waking act, should combine awareness, responsibility and compassion.

** Also translated as:

All component things in the world are changeable. They are not lasting. Work hard to gain your own salvation.

Experience is disappointing; it is through vigilance that you succeed.

Which can also be rendered as this:

All component things in the world are changeable. They are not lasting. Work hard to gain your own salvation.

Updated from a post originally written on 12 March, 2005.