![]()

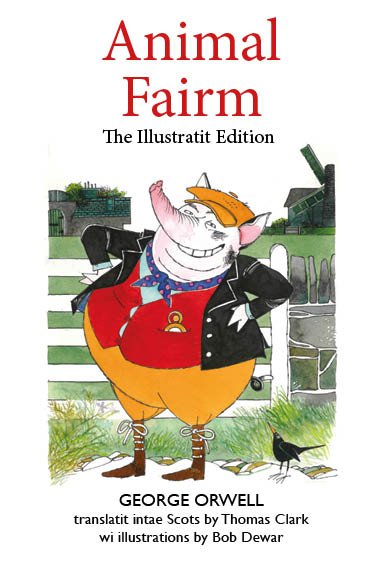

Animal Fairm is a 2022 translation into Scots of George Orwell’s classic satire on Stalinist (and in far too many ways, modern conservative) politics and ideology. As the cover of this edition says, it was “translatit intae Scots by Thomas Clark.” I recently purchased the book for my reading entertainment. And quickly discovered it’s so delightful that it makes me want to read more of and learn more about the language. The book is published by Luath Press, in Edinburgh.

Animal Fairm is a 2022 translation into Scots of George Orwell’s classic satire on Stalinist (and in far too many ways, modern conservative) politics and ideology. As the cover of this edition says, it was “translatit intae Scots by Thomas Clark.” I recently purchased the book for my reading entertainment. And quickly discovered it’s so delightful that it makes me want to read more of and learn more about the language. The book is published by Luath Press, in Edinburgh.

Scots (no, not Scottish) is a variant of English, but it’s a bit more complicated than that, because it owes a lot to both Old and Middle English. Wikipedia tells us it is, “Most commonly spoken in the Scottish Lowlands, Northern Isles and northern Ulster.” It’s also known as Lowland Scots or Broad Scots, to differentiate it from Scottish Standard English (see below). “Modern Scots is a sister language of Modern English, as the two diverged independently from the same source: Early Middle English (1150–1300).” But there’s more to the tale (and there’s that synchronicity with my other recent reading).

Scots, David Crystal writes in his book, The Stories of English (Penguin Books, 2004) is the result of English loyalists, mostly from the north, who fled into Scotland after the Norman Conquest. Their language (Old English) was readily accepted among the Scottish nobles, and soon replaced the mix of French, Latin, and Gaelic that was in use. English (Inglis as it was called) replaced French as the court language before the end of the 14th century and replaced Latin as the parliamentary language in 1411. Gaelic was pushed north. By the end of the 15th century, the term Scots was being used to describe their dialect (it had previously been used for Gaelic).

Crystal adds that the three-century-long war that festered between Scotland and England (begun by Edward I in 1296) helped Scots survive because it became a matter of national pride for the Scottish to speak their own version of the language, one different from the English invaders. Thus they retained more of the ancestral Old English than their southern neighbours.

Unlike other variants and dialects around the globe, Scots has managed to hang on against the growing tide of English, albeit not as fully as I had expected. According to the 2011 Scottish Census, more than 1.5 million people in Scotland could speak Scots, out of approximately 5.4 million inhabitants, or roughly one in four. (in the same census, only about 58,000 still spoke Gaelic). But in 2022, Billy Kay was the first person to address the Scottish Parliament in Scots since 1707. And the Scottish government proposed the Scottish Languages Bill, saying,

No decisions have as yet been taken on how to make progress for Gaelic and Scots and we are actively seeking contributions from across all communities. We are seeking views on how further progress can be made and the views that we receive will assist in shaping the actions taken immediately and over the longer term to deliver on these commitments.

There are four main dialects of Scots, as well as many sub-dialects, according to scotslanguage.com: Insular, Northern, Central, and Southern dialects. That balkanization is a bit like what had happened to Middle English by the time of Chaucer. Central Scots, spoken through the area south and west of the Tay, is the dominant form, much like Chaucer’s London-Kent dialect was the dominant form of Middle English. It’s subdivided into East Central North, East Central South, South Central, and West Central sub-dialects

There are at least 10 sub-dialects, including Dundonian (spoken by inhabitants of Dundee), Doric (undergoing its own renaissance, also called Mid-Northern or Northeast Scots; from Aberdeenshire, Banffshire, Kincardineshire, Moray where it seems one in every two people speak it), Lallans, Buchan, Glesca, and Shetlandic (aka broad or auld Shetland, Shaetlan, and Modern Shetlandic Scots). So I am a tad confused about what I’m trying to read and learn. Clark himself says his work is, “a mixter-maxter o wirkaroonds, sleekit dodges, fly hauf-jouks an better things pauchled aff o better fouk.”

I’m a wee bit overwhelmed: if I want to know more, where do I start learning? Is there a “standard” Scots I can learn? One that’s separate from Scottish English (also called Standard Scottish English, or SSE)? Well, sort of. There’s a blurring between Scots and SSE that the British Library lists as the “so-called Scots-SSE Bipolar Continuum” – combining features and words from English with those of Scots origin. Apparently, a standard form of Scots is still a work in progress and also a battleground for academic stone-throwing. But it’s coming. I think.

Thomas Clark writes in his Owersetter’s Note to Animal Fairm,

There’s a hale buik tae be scrieved aboot the strauchle taewards a Staundart Scots… we’re at a place in oor development as a linguistic community whaur ilka Scots quair has tae, has tae, assume the responsibility o teachin its readers how tae read it.

The Note and his Introduction are worth the price of the book alone, by the way. Aside from his wry, self-deprecating humour, they made me keen to learn more about the language, to learn to read it better, not just read his translation.

I don’t speak Scots, although I can stumble my way through reading most of it. While I grew up, I learned a few Scots words from my grandparents and my mother. I’ve always found them unusual and intriguing and enjoyed their effect on others when I use them (Canadians, it seems, are more likely to recognize them than Americans). I sometimes spice my writing with those few. I may never speak it (with whom would I converse?), but I may learn to better read Scots with reasonable confidence. Plus it represents an intellectual challenge; learning a language keeps the old brain active.

[I’ve long been interested in languages, learning dialects and versions or variants of English, as well as etymologies (readers know my interest in Chaucer’s Middle English). Scots is my latest interest in the field and, as you might imagine, I’ve already ordered some books online…]

It’s also in part because I have Scottish blood in my veins, albeit thinned by the passage of much time into my Canadian self. Still, I feel some prickling of pride in claiming Scottish heritage. My mother’s ancestors —members of the Macdonald clan — arrived in pre-nationhood Nova Scotia (Port Pictou, Cape Breton) from the western Highlands, in 1783. They came aboard the ship the Hector, landing among the 189 settlers, mostly originating from Lochbroom, after a two-month voyage. The family had been driven out of Scotland during the Highland Clearances after the clans lost to the English at Culloden (April 16, 1746, where Clan Donald fought among other clans for Bonnie Prince Charlie). Sometime after that, they met and married other Scottish immigrants in Cape Breton, including at least one from the lowland Dunlops (in Cape Breton by at least 1817). But I digress.*

Animal Farm — the original — is one of those iconic works that everyone should read (and if you haven’t, get yourself a copy right now and start!). Like his justly famous later novel 1984, the earlier Animal Farm is about idealism becoming prey to toxic ideologies. This one has a lighter touch, though. And it’s a very easy read, without the oppressive sense of dread one feels in 1984. Wikipedia describes the novel as,

…a satirical allegorical novella… [that] tells the story of a group of farm animals who rebel against their human farmer, hoping to create a society where the animals can be equal, free, and happy. Ultimately, the rebellion is betrayed, and under the dictatorship of a pig named Napoleon, the farm ends up in a state as bad as it was before.

Seems pretty leftist, until the revolutionaries become the new overlords and worse dictators than the farmers they overthrew. To paraphrase what Lord Action said,

Power tends to corrupt and absolute power corrupts absolutely. Great pigs are almost always bad pigs, even when they exercise influence and not authority; still more when you superadd the tendency of the certainty of corruption by authority.

After his experiences with Communists in the Spanish Civil War, Orwell became disenchanted with the so-called leftist states that grew into authoritarian, rightwing hellholes like Stalin’s USSR had become. Animal Farm was published in 1945, two days after VJ day and the end of WWII. Orwell himself lived only until late January 1950, not quite four months after Mao Zedong declared his new Communist dictatorship, the People’s Republic of China, another authoritarian state that would have been right at home as the subject of Orwell’s satire. As, I imagine, would a USA under Trump (especially if he wins a second term).

Thomas Clark, writing in his introduction to the novella, wrote,

Frae the instant o its first publication aw but seeventy year syne, Animal Fairm, in mony weys, has come tae be oor socio-political urtext — oor wan-singer-wan-sang, oor collective pairty piece, the script we’re doomed tae keep repeatin… George Orwell wisnae scrievin jist tae warn us aff totalitarianism. He wis scrievin tae warn us aboot something that precedes even democracy, the enablin condition for aw we are or howp tae be. Oor language.

Language, English in particular, was also the subject of one of Orwell’s best essays, Politics and the English Language. But let’s not get sidetracked (read it on your own). Translation is also about keeping a language vital and vibrant by bringing new content and variety to its literature. And it also appeals to outsiders who, like me, were attracted to a (possibly readable) version of a familiar book, one that was also timely.

Animal Farm (and Animal Fairm) is both prescient and entertaining with a hefty dose of moral warning. In this age of toxic demagogues and rage-tweeters like Trump and Poilievre peddling their authoritarian, Talibangelist, cult ideologies, it seems like a good time to revisit Orwell’s allegory (and not the animated versions: read the book, dammit). I’m not the first (or likely the last) to point out the relevance of Animal Farm to the Trump era. In 2017, columnist Jonathan Russo wrote in The Observer:

The leaders of Animal Farm maintained thought control by obscuring the facts with smokescreens. In this way, the allegory to the Trump administration is dead on. Executives from Wall Street, once lambasted by Trump as “get[ting] away with murder,” are now in charge. The “currency manipulator” to be punished on Trump’s first day in office, China, is now a strategic ally helping to fend off North Korea.

It’s easy to see the analogy between the book’s leader pig, Napoleon, and Donald Trump, and not merely in their porcine profiles. In fact, I could write a whole post about the analogies, which perhaps I will do for a future post. But let’s not digress too far (my readers here already know my political views about the villainous Trump or the sleazy Poilievre…). In a recent book review, Umais Ahmed wrote,

Animal Farm illustrates how democracy is essential for the protection of individual freedom and the prevention of oppression. The novel shows that when the animals are able to democratically make decisions, they are able to create a society where everyone is treated equally and with respect.

That is, until the pigs took it all away for themselves.

Reading the book in Scots gives me both a chance to learn something new, and to refresh my memory of the original. From the publisher’s website:

George Orwell’s faur-kent novel Animal Fairm, yin o Time magazine’s 100 brawest English-leid novels o aw time, has been translatit intae Scots for the verra first time by Thomas Clark.

When the animals o Manor Fairm cast aff thirldom an tak control frae Mr Jones, they hae howps for a life o freedom an equality. But when the pigs Napoleon and Snawbaw rise tae pouer, the ither animals find oot that they’re mebbe no aw as equal as they’d aince thocht. A tragic political allegory described by Orwell as bein ‘the history o a revolution that went wrang’, this buik is as relevant noo – if no mair sae – as when it wis first set oot.

I can read and understand that, albeit slowly, with the aid of a small Collins Gem Scots Dictionary (from 1995; it’s been reprinted in a “Little Book” format since). Like when I’m reading Middle English, speaking the words aloud can make many clear. It helps to know Orwell’s tale and have a copy of the original handy to compare the words, though (one of the rare times my small e-reader comes in handy because my print version is in a hefty omnibus with his other novels; a tad awkward to read simultaneously with the translation).***

Let’s compare. The first chapter of Orwell’s Animal Farm begins the book thus:

Mr. Jones, of the Manor Farm, had locked the hen-houses for the night, but was too drunk to remember to shut the pop-holes. With the ring of light from his lantern dancing from side to side, he lurched across the yard, kicked off his boots at the back door, drew himself a last glass of beer from the barrel in the scullery, and made his way up to bed, where Mrs. Jones was already snoring.

As soon as the light in the bedroom went out there was a stirring and a fluttering all through the farm buildings.

Translated into Scots by Thomas Clark, it becomes:

Mr. Jones, o the Manor Fairm, had sneckit the hen-hooses for the nicht, but wis ower fou tae mind tae shut the pop-holes. Wi the rim o licht frae his lantern dancin frae side tae side, he swavered across the yaird, drew himsel a last gless o beer frae the barrel in the scullery, and stottert up tae bed, whaur Mrs Jones wis awready snorin.

As suin as the licht in the bedroom went oot there wis a rowstin and a flauchertin aw through the steidins o the fairm.

Most of that I can read and, given the context, understand without great difficulty. I suspect you, dear reader, will also have little difficulty. There are some new or unusual words, but few anyone who watches British TV can’t understand or at least figure out from the context. I don’t foresee any great difficulty with the rest, if I concentrate.**

Among the more famous quotations from the original book:

All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others.

Man is the only creature that consumes without producing. He does not give milk, he does not lay eggs, he is too weak to pull the plough, he cannot run fast enough to catch rabbits.

Yet he is lord of all the animals. He sets them to work, he gives back to them the bare minimum that will prevent them from starving, and the rest he keeps for himself.

Man serves the interests of no creature except himself.

If liberty means anything at all it means the right to tell people what they do not want to hear.

There, comrades, is the answer to all our problems. It is summed up in a single word– Man.

I’ll be looking for these lines in the translation as I read it, to see how they scan. And no doubt annoying Susan when I read them aloud in my faux-Scottish accent when I find them.

There’s a message in Animal Farm that still resonates today, about the perils of demagogues, conservative ideologies, and letting democracy slide. I am glad to see that message still being shared through this translation and hope it reaches a new or perhaps a renewed audience. Even though Clark himself says, “…it’s no easy tae mak the case that a Scots owersettin o Animal Fairm can add sae muckle as a single new reader tae its constituency,” he did add me as a reader, new to his version, even if not to the original. And, I suspect, more will follow.

Highly recommended.

~~~~~

* How long does someone have to have had family in Canada before they are considered native? Is 240 years enough? My father’s family came later, from around Manchester, in northern England, an area full of Viking and Celtic bloodlines that influenced its own Northern dialect. He arrived from England in Canada in 1947, after WWII. There was a Lieutenant Thomas Chadwick on the English side at Culloden, but I have yet to find if he was related (before 1752, the ancestral connections are hazy). I amuse myself by imagining the two halves of my family fighting on opposing sides of that battle.

** A quick pitch for both Acorn and Britbox streaming services. Combined they cost about as much as Netflix, but have a wealth of new and classic shows from the UK. Acorn also has shows from New Zealand, Australia, and some European states. We subscribe to both. No, I don’t get paid by them for this. I just want readers to know about these excellent services because there’s a whole world of entertainment outside US-based streaming that is quite often a lot better viewing.

*** I also read in bed for at least an hour before sleep, where balancing multiple books is even more awkward. We don’t have a TV set in the bedroom because we both read before sleep and consider a TV not only intrusive but somewhat offensive. TV screens already dominate our lives: they are in our living rooms, our kitchens, in bars and restaurants, in box stores, on planes, in our tablets and phones. The bedroom is one place we refuse to let them intrude. And even the one we have is only turned on at dinner to watch one or two select shows, then retire to read in bed.

https://www.thenational.scot/politics/23221272.2023-going-guid-new-year-scots-language/

2023’s going to be a guid new year for the Scots language

…Scots language education is only going from strength to strength and this trend is going to continue into 2023. The Scots Language Centre, for example, alongside partners in the Scottish Government, Education Scotland, the SQA and others, will be holding an online conference on Scots in Education this year… The bill will do more than just tackle linguistic discrimination, as Fyfe noted, but also normalise the use of Scots, particularly in schools, where it can continue to become “a valued part of the curriculum” like any other language.

It’s what you say , not the language or dialect you speak..

I always took Animal Farm as challenging authoritarianism , perhaps Orwell meant otherwise?

That nationalism via language is becoming an issue in this day and age with the, world wide, issues we face , shows , to me, the shallowness if our thinking!!!

TB

https://www.orwellfoundation.com/the-orwell-foundation/orwell/essays-and-other-works/notes-on-nationalism/

George Orwell: Notes on Nationalism…

“By ‘nationalism’ I mean first of all the habit of assuming that human beings can be classified like insects and that whole blocks of millions or tens of millions of people can be confidently labelled ‘good’ or ‘bad’. But secondly – and this is much more important – I mean the habit of identifying oneself with a single nation or other unit, placing it beyond good and evil and recognizing no other duty than that of advancing its interests. Nationalism is not to be confused with patriotism. Both words are normally used in so vague a way that any definition is liable to be challenged, but one must draw a distinction between them, since two different and even opposing ideas are involved. By ‘patriotism’ I mean devotion to a particular place and a particular way of life, which one believes to be the best in the world but has no wish to force on other people. Patriotism is of its nature defensive, both militarily and culturally. Nationalism, on the other hand, is inseparable from the desire for power. The abiding purpose of every nationalist is to secure more power and more prestige, not for himself but for the nation or other unit in which he has chosen to sink his own individuality.”

https://www.luath.co.uk/scots-language/luath-scots-language-learner-an-introduction-to-contemporary-spoken-scots

Just received this book to help me learn Scots…